My father, Pranab Guha Thakurta, was born on 19th March, 1926, in Dacca. 1From as far back as I can remember, Baba’s birthday was always a day of celebration and occasionally a family get-together. For the 16 years that I have learnt to live without him, this day has become for me a time of quiet remembrance. As another year elapsed without him, this year, too, I spent that evening in his room, stretched out in his armchair as he would be, listening to some of his favourite Rabindrasangeet on his music-system that has miraculously survived all these years. And I found myself beginning one of my many imaginary conversations with my father, of a kind that could never happen when we are actually together.

That evening, I wanted to move back in time from the image of that larger-than-life, handsome, elegantly dressed patriarch that I had grown up with, whose discipline and authority was as deeply embedded in our everyday lives as his capacity for care and affection. Instead, I wanted to begin a different conversation with you, Baba, about your childhood years in Dacca that you would hardly ever talk about. I wanted to give you the time and companionship that I never did when we were living in the same home at Salt Lake, and draw out of your reticence the stories of your life that I wish I knew more about.

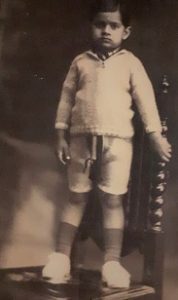

All we have is a single photograph to imagine you as the child who was given the daak-naam (pet name), Gopal. A chubby-faced five year-old stands on a chair, against a painted backdrop of a studio, in a photograph taken around 1930-31. Your face is a give-away: you could not have been very happy being made to pose by standing on that chair. You were formally dressed for this visit to the studio, in a full sleeved sweater, knee length shorts, socks and white shoes. Thinking back from your later fastidious neatness of attire, I feel you would have been a trifle embarrassed by the hanging-out zip-chord of your shorts! What would have been this occasion for this rare solo photograph? Were all your other siblings of the large Guha Thakurta family also similarly posed for individual studio portraits? It could have been your birthday. Or, pushing forward by a year, to the time you were six, it could have been taken for your admission into the prestigious St. Gregory’s High School, 2 that stood just round the corner from your home at No. 30, Lakshmibazar in the old quarters of Dacca. Your father, Bibhu Charan Guha Thakurta, an advocate who started practising at the High Court and the District Court at Sadarghat, Dacca, had moved with his family from the ancestral home at Banaripara in the district of Barisal to this rented house at Lakshmibazar, Dacca, sometime around 1913. But you were the first boy in the family to be admitted to this English-medium missionary school, with its adjacent church and large compound. It is during the time of your admission to St. Gregory’s that your elder cousin who had taken you along put down your birth year as 1927 and the date as 19th May, not March. This mistake, you regretted, remained with you for your entire life. But for the entire Guha Thakurta family, there was no mistaking your real birthday for the official one.

The family into which you were born as the third youngest child was exceptionally large, even by the standards of those times. Bibhu Charan Guha Thakurta did not marry more than once – your mother, Charuprabha (born, Ghosh), alone bore him 16 children between 1900 and 1930. The eldest born, Prabhu Guha-Thakurta (Dada, as you would refer to him), was already an eminent intellectual in the scholarly circles of Dhaka. He had completed his M.A. from Harvard University and Ph.D. from London University, and was a Reader in English in Lucknow University in 1930, when the youngest in the family, Prabir (Badal) was born. Each of your male siblings, barring one of them, had names beginning with P, setting off a chain of P. Guha Thakurtas that would spill from your generation into ours and our next. Your nine sisters were named after the learned and stoic women of ancient Indian mythology – Sabitri, Gayatri, Maitreyi, Atreyi, Leelabati, Sita, Sati, Khana and Arundhati. The family stood out for its liberal, progressive values – especially for the education given to each of these well-groomed, accomplished daughters. After the family moved from Banaripara to Dacca, the elder girls all studied at the Eden Girls High School, and the youngest two were sent to the new Kamrunnesa Girls’ High School at Tikatuly, Dacca, that Bibhu Charan had helped set up as the legal executor of the will and endowment left behind by a Muslim widow of that name.

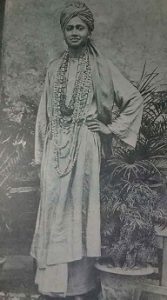

The year you were born would have been a landmark year for the family in Dacca. In February 1926, your second sister, Gayatri, who had always wanted to lead a life of spiritual self-consecration and had been widowed within a year of her marriage, was given permission by your father to accompany her monastic uncle, Swami Paramananda, to the ashrams he had established on the east and west coasts of USA. This decision to let their daughter go – in more sense than one – would have caused waves in the social circles around them. Family history of the Guha Thakurtas had taken a momentous new turn in 1901, when Bibhu Charan’s younger brother, Suresh Chandra (Basanta), left the village home at Banaripara at the age of sixteen to become the last disciple of Swami Vivekananda at Belur Math in Calcutta. Following his stint at the Ramakrishna Mission in Madras, in the winter of 1906, the young and dynamic Swami set sail for the east coast of USA with a senior Ramakrishna Mission monk, to soon embark on his new spiritual career as the head of the Vedanta Centre in Boston, and the new ashrams he would begin at Cohasset in Massachusetts and La Crescenta in California.3 Baba, I know you would have relished this digression into the American destiny of your remarkable ‘Kaka’, Swami Paramananda, with whom you would later have an uncanny family resemblance, who would wield an enormous influence on your entire family. And you would have reflected with me on two historical coincidences – that the year of Swami Paramananda’s departure for the USA, 1906, was also the year of birth of his niece, Gayatri, who was destined to follow in his trail; and that the year of her departure with her uncle coincided with the year of your birth. As she was leaving the Dacca home for the last time for Calcutta, from where she and Swami Paramananda would board the ship on 2 May, 1926, she would smiling remember how her new-born brother Gopal wetted her saree as she was holding him. The special bond that was forged between the two of you was one that you would carry with you till the end of your life.

Two visits of Swami Paramanda to your home in Dacca became the occasion for a set of extraordinary family photographs. In the first photograph from the early months of 1928, the family poses in a setting of a stately mansion, which one imagines to be the courtyard of the Guha Thakurta home at No. 30, Lakshmibazar. (Image 6)You, the youngest in the family at that point of time, are missing from this group. As is your eldest brother, Prabhu, who would have then been in London, your second sister, Gayatri, who would not return to India until 1935, and your fourth brother, Amitabha (Nitai). All your other older siblings are posed around your parents, seated in the middle at two ends, with Swami Paramanda at the centre. On either side of him are the two married girls of the family who would have come to their paternal home for this special occasion. On his left is your eldest sister, Sabitri, married to Sukumar Dutt, nephew of the famous Congress nationalist, Ashwini Kumar Dutta of Barisal, under whose tutelage she became the first woman graduate of Brojomohan College of the town. She had then just moved to Delhi where her husband had joined as a Lecturer of English at Ramjas College. On his right is your third sister, Maitreyi, in her strikingly patterned blouse, who had been married into the wealthy zamindari family of Rays of Mymensingh, and had given birth to the first grandchildren of Bibhu Charan and Charuprabha. The first granddaughter of the family, Roma, sits on the floor, on the extreme right, next to her little aunt, Arundhati (Nuku) – born in 1924, a few months apart, they were and would remain the best of friends. One anecdote sticks in my mind about your brother, Patanjali (Balai), then a ten year old, seated on the floor among his little sisters and niece – a hilarious story passed on to his daughter by your irrepressible sisters, our Pishimas. The story goes that when Balai was born in May 1918, after four consecutive girls, the mid-wife ran in excitement down the streets of Lakshmibazar to the premises of the court of Sadarghat, shouting to her “Babu” that he should come home immediately because a son has been born.

The next family photograph dates to 1935 – it was taken during Swami Paramananda’s month-long stay at the Ananda Ashram at Dacca, where another of his nieces (his widowed sister’s daughter, Charushila) had set up under his initiation a home and school for underprivileged women. On this voyage, he had brought with him Gayatri Devi (who does not appear in this photograph) and an American disciple, Sister Amala, who sits next to him in a nun’s attire. The garlands he wears would have been ones that the Guha Thakurta children would prepare for him each day, from the garden flowers they would collect in the morning. It is unclear whether the photograph is taken in a studio (the figure of a marble statue suggest a studio space) or in a decorated setting within the Guha Thakurta home at Lakshmibazar (as suggested by the foliage, the compound and the room at the back). What I love most about this photograph is you, the smiling nine-year old boy seated on the floor, posing almost exactly as your Shejda, Balai, had in the earlier photograph. He is not part of this family group. The teenaged Balai had got deeply involved with a underground group of revolutionary nationalists in Dacca, and had begun going to sleep with a revolver under his pillow. Your father was alarmed when he discovered this, and soon packed him off to study at Ramjas College in Delhi, under the guardianship of his eldest sister and brother-in-law, Sabitri and Sukumar Dutt. Also missing in the photograph is Pratibhu (Kanai) who had already gone to study at MIT in USA, with the financial aid provided by Swami Paramananda. Two of your sisters standing at the back, Leelabati (Ranu) and Sita (Chokanu), were also soon to set out for New England, in USA, their voyage, stay and college education there to be sponsored again by their monastic uncle. If Swami Paramanada’s continuous patronage and financial support for his nieces and nephews brought on him the sharp criticisms of the Ramkrishna Math and his American community, the journey abroad of two more young, unmarried Guha Thakurta girls would have caused a fresh stir in the family’s social circles. Many of your sisters were accomplished singers and dancers. We were told that, when the dancer Uday Shankar came to perform with his troupe in Dacca, he was so impressed by the performance of your eighth sister, Khana, in an Eden School event that he wanted to take her off to be trained at his new dance school at Almora. But this time, your father’s permission was not forthcoming, and Khana remained where she was.

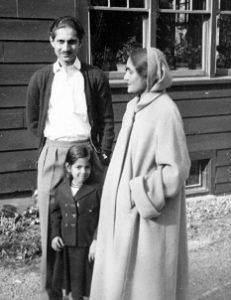

This photograph shows some newer members of the family – your younger sister, Purabi, seated on your right, with your cousin brother in-between, and your younger brother, Prabir (Badal), who is on your mother’s lap. In retrospect, these would have been the last of the family’s stable, happy years in their home at Dacca. Badal, unlike you, was growing up to be really naughty and could get away with anything. Among his notorious mischiefs was his act of pulling down the tablecloth of a specially laid-out meal for Swami Paramananda, leading to the crashing down of all the food as well as the family’s best crockery. It was around this time, perhaps a bit earlier, that you and your brother Badal were taken by your parents on what you said was your only trip to the ancestral home at Banaripara – when, we were told, the two boys were bathed in milk by your widowed aunts as part of their adoration and blessings. What was more exciting for you was your memory from these years of accompanying your father on one of his trips to Calcutta, of being taken to watch a cricket match at Eden Gardens, and of having lunch at the famous Federico Peliti’s Italian restaurant at Dalhousie Square. This was your first trip to Calcutta, and nothing that you had seen in Dacca could compare with the grandeur of the buildings you saw here. I imagine that you were then this lanky boy in a baggy shirt and shorts of this stray photograph, who would have gone all smartly dressed for the Calcutta trip.

Dark clouds soon began to gather on the horizon of the family. The year after the taking of the group photograph of 1935, your younger sister, Purabi, succumbed to an attack of meningitis. The next time you would come to Calcutta was under the shadow of your parents’ ill health and an impending dislocation. In the summer of 1937, your father, then in his early sixties, always a person of frail health, fell seriously ill, and so did your mother. It required that they both moved to Calcutta for treatment and care. Your parents, with the last four children who were still at home – Khana, Arundhati, yourself and Badal – took up a rented place on Amherst Street in north Calcutta, a location that was very close to the Bowbazar home of their daughter, Atreyi and son-in-law, the homeopath Dr. Manmathanath Majumdar (your Rangadi and Mona-da) who took main charge of their treatment. Baba, I remember you occasionally pointing out this old house to me, opposite the Marwari hospital, not far from the Bowbazar crossing, whenever we drove that way. It is here that you father passed at the end of July that year, cared for till his end by your Rangadi and Mona-da. And you, at the age of eleven, was the son who performed his last rites. These memories haunted you – of having to do the mukhagni at the cremation ground, and of later coming out of a bath with your hair neatly combed, which was immediately ruffled up by one of the elders because hair combing, like shaving, was forbidden during this time of mourning. The trauma of the day was life-changing: it created in you a strong aversion to the observance of such rituals, which you were determined never to foist on your children or any others in the family.

Bibhu Charan’s death threw his wife and his four youngest children into a life of uncertainty and erratic movement. At the best of times, the Guha Thakurta had never been wealthy, but there had always been the security of home, a steady source of income, the comforts of an ever- expanding family, and, not least of all, an endless flow of Rabindranath’s songs. Your widowed mother and the four of you never returned to the Lakshmibazar house at Dhaka. Over the next two years, the five of you would move between different rented homes in Kolkata, and would have to rely on the material support provided by relatives. Your years at St. Gregory’s School quickly became a thing of the past, as you were shunted from one Calcutta school to another – from St. Paul’s missionary school on Amherst Street where you studied for a few months in 1937 to the wholly different ambience of the Bengali medium schools, Tirthapati Institution and Jagabandhu Institution, when you all moved to stay in south Kolkata. Finally in the spring of 1940, a new transformative phase of your lives would begin, when your mother relocated with all of you in Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan. Khana, then, had just got married to Suresh Kumar Basu who lived in Santiniketan; Arundhati joined Sangeet Bhavan while also studying for a B.A. degree; and you and Badal joined Patha Bhavan. Santiniketan was a world apart, a genuine ‘abode of peace’ where you could lead a life of utter simplicity, without feeling poor or dependent, and be enriched by an education and cultural upbringing that was unique to the place. There was no question in your mind, Baba, that your time in Santiniketan (1940- 1943) was by far the most unforgettable years of your life. But those stories and the many more to be told – as you went on to study Chemistry at St. Xaviers College, Calcutta and Chemical Engineering at Jadavpur University – will have to wait for other conversations.

When I was in Dhaka in March 2018, I revisited your old school – a still thriving institution with a large new building, where the Church of the Holy Cross, its rear school premises and the playground are what still survives from your time. With a definite house number in hand this time, I moved from the school in search of your childhood house at Lakshmibazar, a densely crowded neighbourhood of the old city. What I found at No. 30 was a set of shops, with no indication of the decrepit residential premises that lay behind them. Entering through the side alley, I found the ramshackled remnants of a large house that is now divided between different families, with the memories of the oldest current resident stretching back no further than the post Independence years. The house, she remembered, had been the property of a certain Mr. Ray, and was first taken over (possibly under the “enemy property” laws) and made into a tax office of the East Pakistan government, before it was parcelled off in sections to different families, whose descendants have been living here since the 1960s. And one section had been demolished a decade or so ago, and the place swallowed up by an adjacent commercial complex. I did not want to know any more. I did wander upstairs to the terrace to get a sense of the original lay-out of the house, of its upper floor of rooms and verandah overlooking the courtyard on the ground floor that had become a storage dump of the shops. Not a trace remained of the two and a half decades that the Guha Thakurta family had spent here, of the house where ten of your siblings were born, including your dearest sister, Arundhati, who would become a renowned actress of the Bengali screen. Not a single memory could I find lingering within the decaying walls of the house. Standing on the terrace of this ruined property, I had the same sense of finality, of a sudden ending, that you must have felt, Baba, when you could never return to the home you left behind in the summer of 1937. Thereafter, your lives rolled on in new directions, and you never really looked back. It was also time for me to move on. There was a flight back to Calcutta I had to take that afternoon. And there were those family group photographs stored away there, that would always stand in for that disappeared home of your childhood.

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Professor of History, was the former Director of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. She lives in Kolkata.

Footnotes

- I have kept to the earlier English spelling of Dacca, in keeping with the time I am writing about

- St. Gregory’s High School had been set up in this very location in Dhaka in 1882 and named after its founder, the Benedictine priest, Reverend Father Gregory de Groote. The school which had been set up mainly for European and Eurasian students, was taken over by Bengali students by the 1920s, especially after 1924 when the school was given its local Board affiliation

- Their life-stories are recounted in Sara Ann Levinsky, A Bridge of Dreams: The Story of Paramananda, a Modern Mystic (Massachussets: Lindisfarne Press, 1984) and Srimata Gayatri Devi, One Life’s Pilgrimage (Cohasset: Vedanta Center, 1977)

Thank you, dear Tapu Pishi for this jewel you have given us!

Thanks Tapu for sharing two wonderful stories. Enjoyed reading them.

Another wonderfully written piece, Didi! Really enjoyed reading it.

Tapudi, thank you so much for sharing these stories that are so close to your heart. You helped me live through moments of joy and despair and as always I am so proud to be a part of this amazing family. Jethi was the most caring person I have ever met and Jethima took every trouble to make our visits to Calcutta during the summer vacations, so special. I remember when Jethu visited us in Barwani and he teared up so many times when he visited our patients in hospital. I believe that he still looks after us from above.

Tepu – my dearest sister ,

Your writing is brilliant & so nostalgic it took me back to staying for so many years with all of you in Lansdowne Court & Kusum Apartments. My Jethu & Jethima’s kindness & all of you making me a part of your family , will always remain with me . There is so much I learnt from Manuda ( music, the most interesting ! ) , from you – art , painting, poetry ( & emotion ! ) & my little Rajabhai who was quietly there all the time .

God Bless you dear sister .

Love .

Jojo