Anonyma: Eine Frau in Berlin (known in the UK as `The downfall of Berlin Anonyma`) is a 2008 German film about an unnamed woman coping with the complex aftermath of the war in 1945. Anonyma is what I choose to call the elderly lady, whose story I am going to relate in the first person. Not only because she did not tell me her name, but also because she spoke to me with a sense of palpable urgency about the same difficult past as we were sitting next to each other in the Inter City Express to Amsterdam1.

Here is her story, or rather the story of her parents:

I was born in 1943, in Oberschlesien (Upper Silesia) which was then a part of the German Reich. After 1945, the Allies gave it to Poland. Even before the war formally ended, a large part of the area became exposed to the approaching Red Army. Rightly fearing Russian retribution, the German speaking part of the population started fleeing westwards.

My family, like hundreds of others, did not want to leave their Heimat. Do you know what this word means? It means home, but much more. It is a geographical and cultural space where you belong, a landscape intimately connected to identity, tradition and nationhood.

After my family was formally expelled by the occupying authorities, there was no choice left. So it came about that we landed at the nearest railway station to board an overcrowded train full of refugees like us, bound for an unspecified destination `somewhere in the west.`

As my parents waited, they saw a big train arrive for the German elite, the high ranking officials and the rich who got their servants to move their expensive furniture and many suitcases inside. Then a smaller train arrived, where middle ranking government servants and the upper middle class could move in with their suitcases. Was this the same ruling elite who had promised us an equal society in a peoples` community of racially pure and culturally homogeneous Third Reich?

The local authorities overseeing the cramped train that we boarded forced all passengers to leave their baggage behind. So none of us had anything but the clothes we were wearing.

Did my family sympathise with the Nazis? I do not know. I never asked them and they never told me. But if they had not been disillusioned before, my parents became disillusioned at that moment.

My mother was the only family member who could get a seat, since she had the two-year-old me to carry. My three brothers, thirteen, nine and six at the time, had to stand all the way through the journey which lasted several days.

Every time the train stopped, my father went out to the platform since he was afraid that the local police would search the train and arrest him. He was a civilian posted in Poland during the war. Anyone posted in Poland was a potential suspect for war crimes.

As their train rolled into the East German city of Dresden, my family could see how the city with its grand architecture had been reduced to rubble by Allied bombing. They were terrified of being forced to alight there, since the people they saw from the window looked in no mood to receive a train full of refugees. Fortunately, the train moved on.

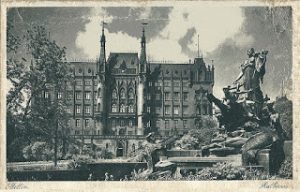

Another scary halt was at Szczecin or Stettin, a Polish city on the river Oder which had been part of Germany from the 18th century till the Red Army occupied it in April 1945. Our train was blocked by the station officials who were Polish. At this point, my father did what was probably the bravest act that he had ever undertaken. Since he could speak Polish, he went ahead and intimidated the officials into letting the train pass. This move probably saved all our lives since during that time German speakers were often treated brutally in areas formerly occupied by the Nazis, in retaliation to the crimes committed by that regime.

Like millions of other refugees from the East, we were `resettled` in Lower Bavaria, which was an economically backward agricultural region. Our first refuge was with a family of peasants, who had been forced by the authorities to take us in. To express their protest against our unwanted presence, they had removed all the floor boards from the room they allotted to us, leaving only a chair and a table for a family of six.

Now my parents realised what is was like to be refugees in their own country. We were humiliated by the local population at every conceivable opportunity – for our accents, for our destitution and our helplessness. The next farmer family that took us in wanted my father to kneel down and beg for food before every meal so that we would keep to our places.

Eventually, my family moved to a community centre for refugees, not unlike the ones that are being provided to the Syrians and others who have arrived here in the last two years. It took many years and hard work for my parents to overcome their grief for what they had lost and to integrate in the society without giving up their self respect. My brothers had to unlearn their accents and keep quiet about their past.

Today, I feel sad and apprehensive to see the same mistakes that our parental generation committed being repeated. When I see that people in Europe are becoming increasingly insular and intolerant, I think of those dark days my family went through. Hatred only begets hatred that engulfs everyone. In the end, only ruins and dehumanisation are left. `

My thoughts on the blurring lines of perpetrators and victims were interrupted at this point by an announcement carried out in German, Dutch and English. It brought me back to the present, still-borderless European Union. My destination had arrived. `”Do not forget my story,” ` said the old lady as I said Auf Wiedersehen.

All pictures courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Dr. Baijayanti Roy is a historian based in Frankfurt.

Loved the story.

I will send mine some day.

Best Purushottama passing through Leiden and Amsterdam

Will look forward to publishing your story Mr.Bilimoria. Thank you for your comments.