This is written by Late Lt. Col. G.L.Bhattacharya in 1978 when he was 60. It has been translated from Bengali by his son, Dr. Pradip Bhattacharya

I do not remember anything before the age of 3. I heard from my mother that I was born at No. 10, Radhanath Bose Lane, Goabagan, in Calcutta, at 20 minutes past 9 in the morning of a Wednesday, (8th Phalgun, 1324 BS, English 20th February 1918). The Calcutta time was 24 minutes in advance of the Railway Time which was called Indian Standard Time. My grandfather (Motilal Bhattacharya) named me Gunindra Lal. My father (Sindhu Lal) was working in Meerut.

My childhood was spent in Meerut. Here my father worked in Military Accounts. He was later transferred to the Accountant General Burma, Rangoon.

A scene of this travelling by ship is my earliest memory. I recall that on the wooden deck my younger sister Hemlata1 and I were trying to walk but could not stand up straight. The ship kept swaying and we clutched on to the railing, to prevent from falling. Father showed me the rear of the deck. Someone had died and was to be buried at sea. Several British and Indian men were standing on both sides of a big coffin covered in a black cloth. A prayer was read from a book as everyone stood in silence, their heads bowed. After that the big coffin was pulled up with a rope and from over the deck’s railing it was slowly lowered into the sea. A little later when everyone had left, I went to see the rear of the ship carefully holding on to the railing -there was no rope and the coffin had disappeared. However, many sharks were following the ship. Father had earlier told me that there were submarines underneath the sea and by hitting ships from below and making holes, destroyed them. I looked for the submarines but could not forget the large box covered in black cloth.

We were in Rangoon till I was 5 years old. We used to stay with my second eldest paternal uncle2 on the first floor of a wooden house. Below, a little to the side, was a Chinese restaurant. Our cooking was done by someone called Indra Thakur, my very dear friend. A few incidents of this time come to mind.

I can see my father very clearly. In the evening, lying down, by the light of a hurricane lamp he would tunefully recite the Mahabharata and I, sitting close by his head, used to listen and keep looking at the book, wishing I could read too. Listening to the reading every day, I gradually came to memorize the text and recite some of the stories. My favourite was Bheem and Duryodhan’s mace-duel. Everyone was scared of father and if he ever got angry, they would all run away and hide. I too used to hide under the table. Only once father caught me, and pretending to punish me, pulled me up by my hair, from where I was hiding. I wasn’t beaten but his intention to scare me was successful.

I began to learn to read and write Bengali from Mother. One day I received a letter from my (paternal) grandmother. Hearing it being read out and after trying to read it myself, I was reminded of her very much—her loving touch, her calling me, “Gunodhor!”(The Talented) Not sharing with anyone, I wrote on a piece of paper my heart’s feelings to her. I had seen that someone, whom every called Postman, came with letters. So, the morning after writing my letter, I waited for him. Immediately on his coming to our door, before he called out to anyone else, I went to him and giving him the paper on which I had written in broken Hindi, explained to him that he must give the letter to my grandmother in Calcutta. I was sure that it was he who had brought grandmother’s letter to me, therefore surely he goes to her and knows her. He looked at me astonished and began trying to explain why it was difficult for him. I explained in details, telling him about my grandmother in Calcutta, whose letter he had brought, and it is to her that this must be given tomorrow. But now breaking into laughter he shouted out, “Babu! Mai-ji! Postman!” My mother and others including my cousins, came and on hearing about my plea to the postman began to laugh. They explained to me how bags were sent by ships. I only understood that this postman did not know my grandmother. Other than this I was in no mood to hear anything else. My secret love for grandmother was exposed and my little bit of writing was an expression of it—realising and thinking of this and my ignorance, I felt slighted. And because it became a subject of poking fun at me, I felt the elders did not understand anything about children at all.

II

In my memory I see myself a child. Along with writing Bengali and reading a little it was decided that I must go to school where the sons and daughters of my uncle used to study. I heard it was “Bengal Academy”. Perched on Indra Thakur’s shoulders I went to school. The first day I was made to sit on the last bench of a class next to my older sister. In front were three more benches and a person with a long white beard and prominent spectacles was teaching. I understood nothing of what he was saying. I noticed that students were going out of class. On asking, I got to know that after taking permission for drinking water they could leave the room. At once I felt extremely thirsty. Irritated, my sister took me outside. When she returned, I too, though unwilling, had to come back inside. A little later I felt thirsty again, but my sister would not go and told me to shut up. I asked her, “Then what will I do? I am so thirsty!” She told me to suck the sleeves of my shirt. I began to do so and by the time the class got over the right sleeve of my shirt was soaked—perhaps it was thirst after all! I remember well how I had totally believed what my sister said.

The next day just before going to school I kept sitting in the bathroom. Everyone started calling out for me, but I was quiet, hoping that they would go away. But my mother did find me out. Indra Thakur took me to school. I had agreed only on Indra Thakur’s words thinking I would be going for a stroll. But he took me to that same school. I would not enter, nor would I let him go. Then a tall, graceful lady came out to the veranda and spoke to me. I liked her but I knew she was not going to teach me. The class teacher was the bearded, humourless gentleman. There was no fear, only rejection. The Headmistress of the school smiled and said, “Why are you leaving? Come!” I said, “But my tummy is aching!” Then she said, “Here there are bathrooms. There will be no problem.” I did not feel like objecting to this and blurted out, “But in that case I am feeling like vomiting!” Then she burst out laughing. Her laughter and her speaking to me from the veranda I did not forget many years later. Perhaps if she had come near and said that she would sit near me and show pictures, or chat, then I would certainly have listened to her. I returned home on Indra Thakur’s shoulders. Everyone at home began to say that I ran away from school. I wasn’t angry or ashamed. I did not like school at all.

After this I recall another scene. Indra Thakur and I are on a boat. The boat is a little away from the shore and for some distance the boat slowly dances and sways. I am looking where Indra Thakur is pointing at: “There is the sea!” Only water for as far as my eyes could see, waves after waves. I watch in amazement at the endless stretch. While looking I must have fallen asleep because later I only remember getting down off the boat, and sitting astride on Indra Thakur’s shoulders as he holds me tight, with my cheek on his head as his sweet voice lulls me back to sleep.

I remember going to Tuktuki’s home in Rangoon. Tuktuki was a girl my age but I remember only her mother who played the piano or organ or pedal harmonium. I loved listening to her play and did not mind the steep climb to their first-floor apartment and once there, Indra Thakur had to persuade me hard to return home.

This is something I have heard. Author Saratchandra Chattopadhyay3 used to work in my father’s office. He did not fancy working. Office work and his world were different, so he was treated somewhat differently too. I have heard that he had come home a few times and apparently had liked my name and that of my younger sister’s. Later in his novel, Path-nirdesh his main character was called “Guni” and heroine “Hemnolini”—our names—might have been an accident.

III

We left Rangoon towards the beginning of 1923. I remember nothing of the journey back. We were in Calcutta till Durga Puja and the account of this time is of the house at Goabagan’s Radhanath Bose Lane.

My grandfather loved to play chess. He had been the Private Tutor of the Crown Prince of the

kingdom of Udaipur in Rajputana and also the Director of Public Instruction of the state. Before that he used to teach Sanskrit and Philosophy in Agra College. There my father was born in the year 1888. We used to call grandfather, “Babu”. He used to write books and followed a strict regimen. Five sons, each one a gazetted officer -with their help and his own pension he lived in retirement, happily.

On Sundays a gathering for playing chess used to be arranged. Grandmother’s brother would visit. We called him “Rejo-Mama”. The match of chess between the two was full of excitement. I used to watch for long hours. I enjoyed the conversation and the occasional ululation, specially when Rejo-Mama was forced to accept defeat. And if he was about to lose, grandfather would enter the bathroom, much to the delight of Rejo-Mama. The matches were held in a big hall, Babu’s room.

I remember the puja in the zamindar’s house in the neighbourhood. A huge, big pandal was put up in the house. A little below where the image stood was a large courtyard where the sacrifice was done. All around were well-dressed, busy people, incense-smoke and music. Amidst all that a person holding a big khanra (curved sword) kept roaring. Two men would come, each bringing a goat. Their heads were fixed in one place. After that with the priest’s waving of lamps, bells ringing, drums sounding and shouting of “Joy Ma!” the sacrifice was done with a single blow. On the day of “Maha-ashtami”(3rd day) there would be several sacrifices. Grandfather said that he did not believe in this type of puja.

One day in the afternoon a photograph of the family was taken. Father wanted that before going to Delhi all of us should be photographed with his parents. The photo was taken on the terrace of the house. Our new attire was khaki half-pant and shirt. We seven brothers and sisters, Grandfather, Grandmother, “Pishima/Thandidi” (father’s sister), father and mother. My elder brother used to live with Grandfather and studied in Calcutta, matriculated from Scottish Church. He was asleep then. I had gone down to call him. With a sulky face he came. I remember his frowning face, evident in the photograph.

This terrace was a place of great fun. In the late afternoons after removing the washed and dried clothes the women of the house—mother, elder brothers’ wives, pishima, elder sister, would sit on a “madur” (reed mat) to dress their hair. One would dress another’s hair with many types of buns—braided, plaited. There was so much of laughter and talk—I could understand nothing and was made to run errands. Someone had not brought hairpins, someone’s comb was lying in her room, and someone else wanted another ribbon— I was asked to fetch them. In the evening, after cleaning up durries were spread. And my uncle’s son would then play the gramophone with a big horn. Many types of folk-plays were aired. Everyone listened with great joy. I used to wonder who sang from inside the box, how do I get to see him! Looking into the horn I used to try and see. I was told that male and female singers lived inside. I believed it and used to wait just in case they came out.

One morning I went with someone to Hedua crossing to hire a carriage from the stand close by. Three carriages were booked for going to Howrah Station the next day. It took three days to reach Delhi. We left by the horse-carriages for the station. At home I was surprised to see my mother and grandmother, weeping. Grandmother caressed me a lot and gave me one rupee. After that it was going to the station, getting on the train and proceeding to Delhi.

There were several stations on the way and father seemed to know them all: what food is good at which station— hot puris, rabri, burfi4! A small compartment was reserved for us—3rd class, but being reserved we were travelling quite comfortably. Only mother was irritated—father was buying a lot of food and she was saying it wasn’t necessary. Still he bought and we ate them all up, causing her much embarrassment. Father praised his own intelligence and we had so much fun.

In the daytime I recall from Bihar onwards on both sides dry, dusty fields and alongside the tracks innumerable spiny manasa trees. Far away were villages and large trees that appeared to be running along with us.

On the third day in the morning we reached Delhi. There two assistants from father’s office had come to the station. From the station on two-wheeled horse-tongas we reached Raisina. On reaching on the 23rd October 1923 we first stayed in No. 9 Ridge Road. All arrangements for cooking were there in the house. A servant named Damodar had accompanied us. After a big meal in the evening all of us fell asleep. The house was quite big, with a small garden inside and a dry toilet, and inexhaustible supply of water. Right in front was a dairy and a small hill that used to called “Ridge”. These are my memories till we moved to Delhi. We stayed in this house for almost five years.

At that time the real capital of India was Shimla. Raisina was being built. All around the huge pillars of the Legislative Assembly were huge wooden scaffolding. The construction of the new Viceroy’s house had begun. North Block was complete, not the South Block. In the distance the War Memorial Arch was coming up.

In front of our house ran a narrow railway line on which small and large engines used to carry broken stones straight via Talkatora and Alexandra Place, over Queen Victoria Road up to near the Purana Quila railway line required for a stadium under construction near Purana Quila. I recall the numbers on the small engines -1, 3 and 11, the big one was 7.

The In front of the house, on the other side of the road, was the Ridge on which were many wild jujube trees with tasty, sweet-and-sour berries. Here during winter, we would wander looking for good, sweet berries. Some distance away was a big water-tank from where water used to be pumped to all the houses. On its left side was quite a thick jungle in which were many “palash” trees. I remember they were truly flame-of-the-forest—densely covered with bright red flowers. Here there was a horse-riding track laid with wood-chips, quite a soft path.. We used to see British ladies and men taking a stroll. Apparently, this Ridge was the final edge of the Aravalli Hills of Rajputana.

Summers would be extremely hot in Raisina. As we were small, perhaps we did not feel the heat as much. At night, we used to sleep in the open ground in front or inside in the courtyard’s garden.

I remember the “aandhi” (dust-storms). From about 4 to 6 in the afternoon, suddenly on the western horizon would rise a reddish ochre cloud filling the sky. Along with it rose the loud cawing of crows and their flying about hither-thither restlessly. That dense cloud rising at high speed in the sky would reach overhead. The dust-storm followed. To stand outside was extremely difficult. I used to try but the blast of the wind would push me back. After that it would gather plenty of dust. Our mouths, eyes and ears would get filled with dust. If the house-doors were shut, it was difficult to open them. Immediately after the storm began we would somehow flee inside the house. That wind would keep pushing against the bolted doors, as if saying, “Open up! Open up!” Nothing at all could be seen outside the glass windows, only a storm of red dust blowing, like a cyclone. After about half an hour slowly, gradually, when the fury of the storm lessened, then suddenly it would rain very hard. It would remain sullenly hot and till about midnight, our bodies would burn from the heat. But there was plenty of water in the taps and we would bathe three to four times from the afternoon onwards. Another problem was cleaning the dust in the rooms. Images of these storms, and sounds remain vivid in my mind.

IV

There was only one market. Its name was “Gol Market”. Inside were some vegetable and fruit shops and a meat shop owned by a Muslim. Outside where there were shops of atta, rice, ghee etc. Near that in a small shop a Sikh used to sell meat. Good meat was 8 annas a seer5. Even better meat was available at Ajmeri Gate. As we were a big family, father used to bring 3 seers of meat. For Christmas it would be gram-fed or “dumba”6 meat. On cooling it would congeal, full of ghee or fat. But eating it with hot rotis tasted like amrita (ambrosia). Also, one felt extremely hungry. We brothers used to eat 12 to 18 chapatis, each. Ferrying fish from Okhla, a Mussulman named “Sadhu” used to supply almost daily. The head of the fish was free. Fish, too, was 8 annas a seer. Excellent atta was 8 seers a rupee. Fine Basmati rice was 7 rupees a maund7 and ghee 2 rupees a seer. Father would bring monthly provisions from the city. I used to go with him on a tonga. Then the fixed official rate for a tonga was 12 annas. 6 annas for the first and the next hour. From Lal Kuan and Khari Baoli atta, rice, masala, ghee etc., and right next door from big vegetable shops about ½ maund potatoes and other vegetables. From Chandni Chowk came sweets: Sohan Halwa, laddu, and for mother many types of fried dal from Ghantewala’s shop. On the way back, father would buy a Hindustan Times newspaper. At home we used to read Pioneer. There was no other English daily in Delhi.

On the Ridge, a little north from our house higher up on that road, a lot of the hill was being broken down and flattened. Daily in the morning groups of Delhi village women would come singing. In summer, at noon one or two of them would come and sit in our veranda to eat. Two or three dry, thick rotis (almost half an inch thick), raw onion and red chillies—this was their lunch. If spoken to they would laugh a lot because they did not speak proper Hindi. They belonged to the Gujar tribe, speaking broken Hindi, sounded quite sweet. I heard they were working because a temple was being built by the businessman Birla. The women workers got 6 annas a day and the men got 8 annas. From this, however, each had to donate daily one anna for the temple! Even at that young age I felt bad about this. I had heard Birla was a wealthy man. To deduct money forcibly in this fashion I felt was unjust and I felt no respect for this temple. However, in the evening when the men and women in separate bands walked back southwards by the road in front singing away, then it felt extremely nice –the words of their songs and the way they walked, swaying. On their heads they carried iron pans in which they used to take broken stones for spreading. They came from quite far away, I had no idea where.

In the year 1924, probably in the month of March, father decided that I must get admitted to school. There were two schools: MB School and a school for Bengalis. I was to be admitted in the Bengali school and off I went with father one day. On the way someone came and said something to father. I heard the wife of someone of father’s office had committed suicide in the morning setting fire to kerosene possibly in Tughlak Place. Father told me to return home because he had to go to help. My going to a regular school having been prevented, I was not sad at all. I have already said that in Rangoon I did not like school at all.

To the north of our house was Ranjit Place. In house No. 1 there lived Subrata Chakrabarti, an assistant in father’s office. As taught by father, we used to call everyone “Kaka-babu” (Uncle) and their wives were our “Kakima” (Aunt).

At this No. 1 Ranjit Place Subrata Babu’s son Dulu or Sukumar became my intimate friend. Subrata Babu’s relative was Ajit-da. He was possibly in class 8 of that Bengali school. The Headmaster was Mr. Ganguli. At father’s bidding after a few days it was Ajit-da who got me admitted to school in class 4. The exams were just a few days later. About attending classes I only remember the grave and calm Mr. Ganguli’s class. I used to sit on the rear bench and listen, understanding nothing at all. No one used to ask me any question.

Of the exams I only remember the day of Arithmetic. I knew only addition and subtraction. On the day of the test, father saw that we also had multiplication and division. On the morning of the same day father taught me to multiply and divide. I learnt with tearful eyes. At the time of the test, however, there was no simple addition, subtraction or multiplication and division at all. In the question paper were rupees, annas, pie additions and some problems. I could not tackle a single one of the sums. I remember I was writing in the copybook when I saw that one or two boys asked for and got more paper. I thought this must be the rule, so I too asked for an extra paper and actually got it. But I could only write my name.

I remember the results of the exam in the class. The teacher, Noni-babu, was calling out names and announcing the marks. Hearing that my mark was zero I was not surprised, but out of shame my face had become hot. In other subjects I heard I had passed. However, I was not beaten by father at home.

Immediately after this test we went to Calcutta during father’s leave, again by train. On the way my father’s eldest brother boarded, probably from Aligarh. He too was going for his youngest daughter was to get married.

I remember in the train my uncle asked me about my studies. Very innocently I told him that I had scored zero in Arithmetic. He looked very grave, in his white beard. All of us were in great awe of him. Hearing of my getting zero in Arithmetic he said at once, “Then what else now—eat gur-muri (molasses and puffed rice)!” At first I understood nothing. Later I felt perhaps he had mocked my mother’s parents, because my maternal grandfather belonged to the village Geedhgram in Burdwan district. Molasses, puffed rice, kheer etc., were his favourites. He used to cultivate a lot of land himself. Thinking of this I felt that uncle had decided that my studies could not improve at all. At such a tender age (almost 7) somehow I lost all respect for him for his sarcastic words.

Returning from Calcutta I began to go to school again, possibly in class 4 again. My younger brother Robi8 also got admitted in class 1. He was about 2 ½ years younger to me. As he was not good in studies, father engaged a private tutor. He used to come to teach me and my younger sister Hemlata in the evening. I remember that I used to get only the smell of milk and sugar from his mouth. At that time I had a fixed idea that I had limited intelligence9. However, I made many friends—Sukumar, Biraj, Shitangshu, Satyabrata.

From the year 1926 I began to get periodically Malaria fever. There was terrible shivering, one quilt atop another, and upon them some younger brother or sister would lie down. I remember the fever rose to 108.2 degrees once. Immediately after the shivering stopped the fever would shoot up very much and often after an hour would become normal. I had become quite weak. I had a lot of quinine mixture and from one Harsha-Babu homeopathic medicines. By no means would this fever leave me. It would come almost every week.

Harsha Kakababu (uncle) lived at Ranjit Place, probably at No. 15. Every morning he used to give homeopathic medicine to all. My duty was to get medicines from him for myself and my brothers and sisters before going to school. One day, after asking many people many types of questions, he prepared small paper packets. I was his last patient. He was preparing medicines and saying how good homeopathic medicine was—could do all types of treatment. I remember asking him, “Kaka-babu, is there any medicine to increase intelligence?” Remaining silent a little he said, “Yes, of course there is!” Going home after that one day finding my father alone I had said, “Harsha Kakababu has said there is medicine for increasing intelligence too. Wouldn’t it be good if I take it?” Father did not give any reply to this at all. I felt, “Alas, no one at all wants that my intelligence should increase a little and I do a little better in school studies!”

In the year 1926/27 father decided that he would send me on a change of climate. My elder uncle’s son Moni-dada and my elder brother Noni-dada had come from Calcutta. My elder brother was studying in a college in Calcutta, studying M.A. in Philosophy to become a professor. It was being decided that I go to Calcutta with them. Father was talking with them about me. I was outside the room, listening. On my lap was my younger brother Amarendra10. I was keeping him quiet, very curious about what father would decide. I heard I would have to go with them. And father spoke about my weakness in arithmetic and simultaneously said that I was quite ‘intelligent”. I knew that in English “intelligent” meant clever or sharp. This was the first time I heard something a little good about myself—that too from my father. Hearing this I felt very happy. And to prove that I was good began to make great efforts to keep my little brother—who was on my lap—quiet. This was my first prize!

Before this I used to hear from my mother in the afternoon the poem, “Meghnad-Badh Kabya”11. Mother used to read books father had bought. Besides this, two volumes of the Kashidasi Mahabharata I had read many times and several passages had got committed to memory by themselves. At home a portrait of Satyanarayana was very dear to me. It seemed as if the portrait were smeared with wealth, beauty and friendship. Besides this mother would observe “broto” (vows) and a book titled “Meyeder Broto katha”12. that mother used to read I liked very much. Father had bought me some Bengali books like Asutosh’s autobiography13. in Bengali. I used to be full of respect reading about such great people. I missed my friends in Calcutta. But on coming to Calcutta my fever really stopped. I lived with my grandparents for a year, and the experience remained deeply etched in my memory.

After retiring from service, Lt. Col. Bhattacharya took the Ll.B. degree from Calcutta University to

prove to himself that his mental faculties were intact and practised in Bankshall Court and

Calcutta High Court till 1982. He also studied the B.Ed. course in St. Xavier’s College when

his son was a Lecturer in English there and also taught spoken English in the Institute of

English.

He also written extensively. His writings include:

The Prophet of Islam, inspired by Sri Aurobindo calling him “Yogi shrestha” (Best of yogis).

Krishna of the Gita: reflections and the necessity for re-grouping the text of the Gita

(www.writersworkshopindia.com).

A response to K.D. Sethna’s “Two Puzzles in the Gita” in the light of his own sadhana.

A seven act Bengali play on the last nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daulah based on extensive

research (Dasgupta & Co. 54/3 College Street, Kolkata-700073).

A treatise on the Portuguese Empire in India (unpublished); Memoirs of his early years

(unpublished); On the parable of the widow’s mite in the Gospel of St. Mark for a book by

Fr. Oswald Summerton S.J.

Born in 1918, Lt. Col. Bhattacharya passed away in 1988

Footnotes

- Married to Satish Chandra Mohapatra, of Baripada, Orissa

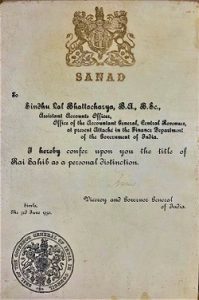

- Sindhulal was the 3rd son of Motilal. He was conferred the title ‘Rai Sahib,’ and was Asst. Accuntant General in Delhi when he died

- Renowned novelist of Bengal

- Different kinds of Indian sweets

- 0.9kg

- Fat-tailed sheep

- 37kgs

- Rabindralal who retired from the Indian Air Force

- Later this changed. Raisina Bengali High School gave him a medal for standing 6 th in the H.S. Board exam 1933. In ISc he stood 1 st in the University 1935; in BSc 1 st in the University 1937. His father suddenly died. He shifted to Arts and took his MA in English in the II class in 1939 from St. Stephen’s College, Delhi, where he also lectured 1938-40. In 1968 he got the LLB degree from Calcutta University and practised law

- Amarendra Lal who retired from the Indian Meteorological Department

- An epic by Michael Madhusudan Dutt on the killing of Ravana’s son Meghnad or Indrajit

- Tales of vows/fasts for women

- Sir Asutosh Mukherjee, Vice-Chancellor, Calcutta University for five terms