I wasn’t the midnight’s child, arriving three weeks later in 1947 when India was in the cusp of transition; many things had changed while some hadn’t. Politics was relatively straightforward; feelings and allegiances of ordinary men and women were far more complicated. The outcome was that I grew up to call my father Daddy, not Baba, the Bengali equivalent. Born in Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh where the language was Hindi I spent a lot of time with my ayah from Madras, whose mother tongue was Tamil, and who taught me to call my Baba, Daddy. My father who had joined the British Army in 1942 and had struck up great camaraderie with British officers, liked being called Daddy, his acknowledgement of the colonists. ‘Daddy’ remained and was continued by my younger sisters.

Daddy was born in 1919. However, officially his birthday was put down as January 1, 1920. How this date was decided on, remained a mystery. In all likelihood, his brother, 10 years older than him whom I called Jethamoni, took him to school for the first time. In a family of five children, it was not uncommon for the eldest sibling to take on the responsibilities of the younger ones, in this case the youngest. Between the two brothers were three sisters, we called Boropishi, Mejopishi and Chotopishi. Their parents, Dadu and Thakuma were not too fussed over these trivial matters of getting their children to school.

What a contrast that was to my own experience of the first-born son being admitted to school for the first time! It was in Ambala, in the year 1951, possibly. My parents’ friend, Col. (Dr) P Sarkar had a movie camera that was marshalled to capture the significant moment of his daughter Maya and me joining school. Such were the changed times, a leap of 30 years.

Back to ascertaining Daddy’s date of birth. I quizzed Thakuma about it. She confirmed that the year was 1919 (the war had ended quite sometimes back) but she wasn’t sure of the date. She could only recollect that it was around Rathayatra1 and that she was in severe pain. I did a little research of my own and found that if one takes a hundred year span, dates repeat after a period of about 20 years or so. In 2019 the Rathayatra was on 4th July. Going back a hundred years, one can safely assume that Rathayatra in 1919 was either the 4th or the 5th of July, the day Daddy was born.

We did try and celebrate his birthday in July, but for some reason it did not continue. Daddy’s regimental officers made it a point to have a party at our house on the 1st of January. I vividly remember these grand celebrations particularly in Udhampur in Kashmir and then in Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh and Anandparvath in Delhi. So, July was bid farewell and 1st January came to stay as his birthday. Celebrations petered out after he retired from regular army and we his children moved out of home. Instead, we always celebrated Daddy and Ma’s wedding anniversary on the 16th of August whenever we were together. They married in 1946, two days after the Great Calcutta Killings, the worst riots witnessed in the city. That is a story for another time.

II

Daddy’s place of birth was Krishnannagar Nadia, more than 170 kms from where his family was originally from in an age when mobility was restricted. So, I have no idea as to how Thakuma came to be there for her delivery. Had her parents moved home there? Daddy thought it was because Dadu’s uncle who had joined the police in British India was posted there.

Daddy belonged to the Ghosh Roy Chowdhury family of Idilpur a town in Madaripur subdivision of the Faridpur district, in East Bengal, at present, Bangladesh. The village was called Daser Jongol which I always liked to imagine something like the Sherwood Forest, though the literal meaning was a lot less romantic-abode of servants of God.

After completing school, Daddy went for his undergraduate studies to a College in Chittagong, a port city on the Bay of Bengal, about 340 kms south of Faridpur. This is where his father, Monmohan Roy Chowdhury was transferred. Joining the police service became something of a tradition in the family, for Monmohan possibly inspired by his uncle, followed suit. After all, the uncle had risen to become the first Bengali Deputy Superintendent of Police. Sadly, he died young in harness, leaving the extended family dependent on him in dire straits. As was customary then, the other male members of the family did very little and land owning was not adequate. Jethamoni, Sudhir Chandra Roy Chowdhury followed in his father’s footsteps, joining the police and remaining with the service till retirement.

III

Daddy completed his graduation from Chittagong Government College which was a very well known institution. Among his professors was Padmini Rudra who was also the Principal and was held in high esteem in the field of education.

He was recruited through the King’s Commission’s into the army and was commissioned on 5th of August 1942 as an officer in the Corps of Signal. One of his early postings was to the North West Province (presently in Pakistan). He often used to regale us with stories of the exotic land and descriptions of their amazing Peshwari food, particularly kebabs and Biryani. Daddy dropped the Chowdhury from his surname, though Jethamoni and his family continued with the grander title of Roy Chowdhury.

Daddy was posted to various places in the course of his career in the army- Ranchi, Lucknow where I was born, Mhow, then Ambala where my sister Urmi was born, Delhi which was Tapti’s birthplace, thereafter Jabalpur and Delhi again. Shortly before retirement Daddy was in Kharagpur and Kalyani in West Bengal and finally Kolkata. In between he was posted to Udhampur which at that time was a nonfamily station and Ma with the three of us remained in Delhi, visiting Udhampur twice a year during holidays.

He was an Instructor at Signal Training Institute Mhow between 1949 to 1950. I was 2 or 3 years old and my sisters weren’t born yet. Ma used to tell us that though he was the Instructor, Daddy treated all the junior trainees as his younger brothers with a lot of affection, providing them with guidance as and when they needed. He was always very proud of the fact that many of his students went up to the general rank in the army. Our house in Mhow was a get together point for these trainee officers, especially the Bengali men who often visited, pestering Ma for Bengali food they sorely missed.

Daddy’s career was chequered. He was very popular with his junior officers and staff members which became a source of envy among some of his colleagues and senior officers, for which he suffered setbacks. He was also very outspoken and there had been instances where he had major differences with a couple of his superiors that he did not hesitate to express. One of his bosses ensured that his promotion got delayed which was a sore point in his otherwise cherished career. His contemporaries got their promotions in time whereas his was held back. In the normal course, he should have retired at least one perhaps two ranks higher.

Rummaging through his papers, I came across information that he had never shared with us, taking immense pride in all achievements, however trivial of his children instead. He had been decorated with a number of medals in the course of his service life. They included, War medal in 1945, Independent medal, India service medal, Sainya Seva medal, Service medal with clasp J&K, Raksha medal 65.

Daddy was a person of strict principles and knowingly could not think of harming anyone. He would go all out to help people even at his own expense. He took care of his close relatives. I know that he had had to incur quite bit of expenditure to cater to the needs of his extended family after partition in 1947, as many of them spent months with my parents. Ma related how Daddy was forced to borrow so that there was enough food for everyone on the table. He then spent years repaying the loans. During Pujas we ( 3 of us) would wear new clothes as per tradition, but Ma and Daddy abstained from buying new clothes. It was much later that I realised the reason- he was hard pressed for money, having to pay off his debts.

IV

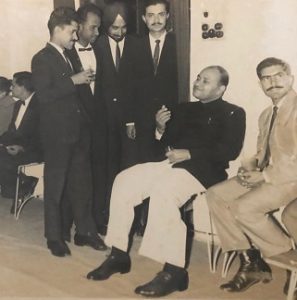

Daddy was quite a stickler for discipline at home but for his juniors and subordinates he was a friend and guide. To the very end of his life these friends stood by him and I and my siblings always felt that they were part of our family. With Bengali families, the uncles and aunties quickly changed to Kaka and Kakima.

He played Hockey for Corps of Signal. Unfortunately by the time Signals became eligible to compete in the national Beighton cup competition in Calcutta, by the standard of the game, he was too old. I am sure otherwise he would surely have been in the team. The Corp of Signals hockey team was probably the best team amongst the army regimental teams, and I had seen Daddy representing the team. I was very young and have faint memories but later on when I met some Signals hockey players, they did mention that Daddy was their mentor and the team owed a lot to his experience and advice.

V

After retiring from the army, Daddy worked in Agarpara Jute Mills for a couple of years. We all lived in a big apartment inside the Jute Mill premises. Urmi’s marriage took place here and when our son Jishnu was born in 1974, this was his first home.

Thereafter he worked with Lutheran World Service in Siliguri from 1977 to 1984 as the Field Administrator. He supervised a number of projects which L W S undertook for the welfare of the people in North Bengal. Sericulture, silk rearing and farming was his passion and he established quite a few sericulture units in that area including a fairly large unit in the Jalpaiguri district. He had acquired considerable knowledge in this field and was invited by the Government of Nepal to help them in their sericulture development. However, he did not want to take up any further assignment and was keenly looking forward to enjoying his superannuation in Kalyani.

Till the very end, Daddy remained alert, his memory intact. His signature on cheques did not waver ever. We miss him always though we also feel he is still with us, particularly when in Kalyani. Malabika, my wife, always says that when visiting Kalyani she feels close to Daddy, as if he is around everywhere This is not a biography of my father but my memories of our Daddy, and all the feelings and emotions they evoke.

Sudeep Roy is a retired bureaucrat. He is now a public speaker and lives in Kolkata.