Continued from part I ……

Dad had been hearing about partition for quite some time. Finally it came to be.

On 14 August, 1947, just before noon, all of us are gathered on the first floor balcony. The long, narrow red carpet especially laid out in front of the main entrance of the Sindh Assembly building to welcome the honourable guests is firmly etched in my memory. We go up to the balcony for a clearer view.

The name of Quaid-e-Azam1, Mr. Muhammed Ali Jinnah’ is on every lip. He is wearing a light Nehru jacket2. A delicate looking lady is standing beside him. I am told that she is his sister, Fatima Jinnah. She is in traditional attire, wearing what seemed like a ‘lenhga-choli’ (long skirt and blouse) with her head gracefully covered with her ‘dupatta’ (long wrap). Brother and sister are standing at the head of a long row of uniformed people.

Soon a black, 4-horse drawn carriage comes into view; the white horses moving in perfect tandem, along the pathway. The carriage comes to a halt besides the red carpet. The Jinnahs walk up to the carriage door, which is in our direct line of view. Viceroy Lord Mountbatten and Vicereine Lady Mountbatten alight and move forward to shake Mr. Jinnah’s extended hand. I distinctly remember Lady Mountbatten’s silken white dress, draping elegantly her slim figure. A sash across the Lady’s left shoulder ends in a large bow at her waist. Lord Mountbatten is resplendent in his smart dark-coloured uniform.

Hands are shaken; a band plays some music. They walk along the red carpet to the entrance of the Sindh Assembly building, and walk into the hall through the entrance under the huge dome, bathed in bright sunshine. The dignitaries go inside the Assembly building.

After they come out, the flag of Pakistan goes up for the first time. Bugles blow, people shake hands. And a new nation, Pakistan is born,

Not many are alive today who have witnessed this most seminal moment in history. I was lucky to be at that particular spot, at that particular time on that particular date. India had been wrenched apart into two. A new and separate nation, Pakistan, was born that day on the Indian subcontinent.

All of us retreat indoors. My parents and some neighbours talk about matters, softly, above our little heads.

Instead of celebrations on the day that Pakistan is born, there are ugly scenes of fighting, looting and arson all over. A curfew is declared. I cannot fathom the cause of all the tensions in the air.

People from the staff quarters come to our compound with daggers. “Abhi sooraj dhalney doh, phir dekhna kya hota hai”. (Just wait till sundown, then you will see what happens),’ they threaten.

By the evening, the threat turns into reality. Ugly fights break out between Muslims and Hindus. The Muslim employees of the Sindh Assembly, residing in quarters across the bordering wall, run amok looting their Hindu neighbours. They carry away clothes, small furniture, utensils, radios and other items of domestic use. After dumping them in the centre of the courtyard, they run back to loot some more. The women from the Muslim quarters rush into the central courtyard and scramble back with arms full of looted stuff. As the sun sets in the west, a ring of fire is seen all around, in the distance.

Huge flames leap up in the darkening skies. We return to our rooms but none of us can sleep. My baby brother, Gul, cries incessantly. My younger sister, Indu, wanders around aimlessly, dropping her doll, picking it up and cuddling it in her arms. I am sick with fear and lie down with my head in Mummy’s lap. She covers my eyes and ears with the end of her ‘pallu’ (End of a sari that hangs behind the shoulder and is also used to cover the head) in an effort to erase the ugly scene from across the boundary wall. I clutch her sari tightly in my hand.

Communal hatred raises its ugly head and arson, looting and rioting continue for the next few days.

Threats from some neighbors echo in our ears, “Hand over your jewellery, or else …” and a knife gleams in the light of the flames around us

The neighbors from our gated community gather in our house. They bring all their family jewellery tied up in little ‘potlis’ (pouches) which they hand over to my Dad. “If the goons come, hand over these so that they may leave us in peace”.

We were born Hindus but we read the Guru Granth Sahib3 and followed the teachings of a Sufi Pir 4, Naseer Fakir of Jallalani Sharif in central Sindh, far away from Karachi. The moment the news of our grim situation reached him, he dispatched two of his attendants. Dad was at evening prayers when the two men came with guns and shouted out his name. He ran downstairs to meet them. They told him that they had come to protect us.

“No harm will come to you”, they said. I do not remember for how long they stayed but they guarded our premises. No unruly element entered our compound and our neighbors were able to return to their homes with their jewellery.

The Gandhian school, where I studied, was near the Sindh Assembly. It was shut down immediately because of the riots, and curfew was imposed throughout the city.

Dad contemplated leaving for India. The Sufi Pir sent word to him that he need not leave. His men would protect us and we could stay; and we did for over a month till end of September, 1947.

No cars or ‘tongas’ (single horse carriages) are to be seen on the roads. We have no telephone in the house. Dad borrows a bicycle and goes out to survey the situation. He is away for a few hours and all of us are nervous.

My sister and I are admitted to a convent school and ride the school bus. Having studied in the Sindhi medium Hardevi High School, we are not too fluent in English. The girls at the convent pull our hair and say, “Go to your country”! We wonder what that means because Karachi is our home and we still think that we are in our own country

Widespread looting and arson all around continue for days. I can feel the fear and tension mounting in my parents’ hearts.

We darken our homes and all of us climb on to our “peengho” (swinging bed). My hands are cold, and I am shivering. Mummy senses my fear and reaches out to cover me with the ‘pallu’ of her sari. The swing has the head of Krishna with a peacock feather adorning it. Amma, my Grandmother, puts her hand to it and then touches her head. She has moved in with us for safety. Dad holds a photograph of Sain (patron Saint) in his favourite saffron turban and white salwar-kameez. He stares into the eyes in the photo. “Raham kayo” (Have mercy)”, he whispers.

THE EXODUS

Curtain call to the last scene

It is the morning of the fateful day in September when the 5 of us get on a horse carriage and head towards the shipyard. Gul is in Mummy’s lap. Indu and I are clutching each other’s hands tightly. Dad is tense with anxiety, his lips tightly pressed.

The vehicle races ahead on empty roads. Trees roll past, waving us a silent farewell.

(Karachi’s total population at that time could not have been more than 18,000).

Fearful and sobbing, I clutch the folds of Mummy’s chiffon sari and she envelops me in its pleats, soothing my fears and promising to keep me safe.

The land of Ralli quilts, the Sufi Pirs, the open-hearted village people of Jallani Sharif are left behind forever in what is now Pakistan. My parents join the wave of refugees fleeing to the land, which, the powers now in command, call India.

I remember seeing the ship for the first time. My fear and sorrow strangely give way to great excitement over going on board and sailing in the ship.

As we walk up the rickety gangway around ten or eleven o’clock in the morning, we encounter many guards and are searched. We have one aluminium trunk with three outfits for each one of us and a couple of chappals and a pair of shoes. A foot operated Pfaff sewing machine of German make, on which Mummy did all her sewing, is wrapped in woolen blankets got from Bangkok and stuffed inside a large copper water container. We were allowed only one suitcase per family. Mother took the sewing machine, hoping and praying that it will be allowed to go through. And, it was!

Hundreds of people are on board, ahead of us, and are lining the passages to get one last glimpse of the land they might never see again. We go into a cabin with four berths. Gul being only three, will be sleeping with Mummy, of course. We join the crowds waving tearful goodbyes to friends. We wait for Mohammed Sheikh, Dad’s friend and colleague who had promised to bring us lunch for our journey ahead, and my mother’s jewellery and some cash – he never turned up.

Our wait is in vain. No lunch, (no jewellery). Dad and Mum warn me, eldest of the three: “Do not utter a word”.

Dinner is a hushed affair. The food is strange. In any case, nobody is interested in eating because we are very scared. None of us know exactly what to expect. There is a tight knot in my stomach, the way it had been on the evening of August 14, 1947 when Karachi was burning around us.

The engines of the ship are revved up, creating a deafening and dizzying whir and making my palpitating heart, beat faster. A thousand worries swarm my mind. What will happen to Mummy’s jewellery, which Mohammed Sheikh had promised to bring? I do not dare to bring my anxiety to my lips.

Gul and Indu are half asleep but I remain fearful and tense, never having been on a long boat ride before with so many people. In the cabin, I am given a bed by the side of a porthole so I can look out at the sea! That keeps me awake and happy…

Half of the passengers on board lie in the passages, the rest sprawl on the decks, crowded and packed right to the railings.

Weary and worried, we crawl into our beds. Mum and Dad recite the usual prayers with us

Sleep eludes my weary eyes. I can sense the negative tension in the air, bringing silent tears streaming down my cheeks.

It is getting dark and one cannot see much through the portholes, beyond the waves crested with frothy peaks rising and falling gently as the ship does the knots. Gul and Indu finally fall asleep, but I remain disturbed by the anxious conversation between my parents in hushed tones. The rolling of the ship on the mildly rough sea eventually lulls me to sleep.

We had hardly slept, it seems, before we are nudged awake.

At sunrise, the sun looks like a shiny bright round platter ready to take a dip in the ocean. A couple of seagulls fly across the sun, waving their feathers and perhaps wishing us well. Gul and Indu become particularly chirpy. My mind lingers on our parents’ hushed tones in the night. What had they been discussing?

There is light banter about bathing, fresh clothes, food. One by one we bathe quickly. When we open the door to go to the dining room for breakfast, a shocking sight meets our eyes. Hordes of people are lying all over the floor of the passage. Some are asleep, some are groaning, some are vomiting. There is not an inch of space to put one’s foot down.

Dad quickly shuts the cabin door and whispers something to Mum. All of us sit on the lower bunks and he steps out with a warning: “Don’t open the door to anyone, I will be back soon. I am taking the key.” Gul senses the tension and bursts into tears. Mummy seats her pet on her lap and tries to soothe him.

It seems an eternity before the key turns in the door lock.

Dad is back with a tray laden with assorted breads, spreads and a pot of tea. We sit down and eat. The food, surprisingly, tastes good. The crockery and the cutlery are sent back to the dining hall.

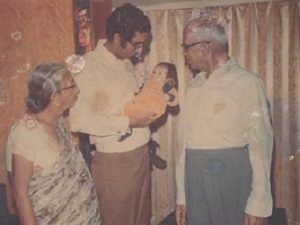

What next? Gul climbs back into Mum’s lap. Dad seats Indu on to his, and puts his arm around my shoulders. “You be brave. You are a big girl, Shamlu.” He shows my age on the fingers of his hands. “We will be okay”, he continues, “Let us go out and see what is happening”.

The galleys are still crowded. We inch our way through the human bodies, making sure not to step on anyone. The upper deck is crowded with people, some sleeping along the edge of the passages while others are standing by the railings and staring at the mass of blue stretching above and below. The sky and the sea merge into each other, in the distance. The ship rolls and I fear for the people leaning against the railings. What if they fall off? The vessel would not even stop.

I try to shut out the fearsome thought by recalling happy memories of picnics on Clifton Beach in Karachi.

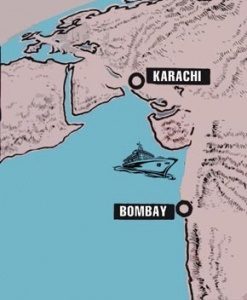

Our journey from Karachi to Bombay takes two nights. What I wonder now is, how did we survive it? It was raining very heavily when we docked in Bombay. Thousands of people lay huddled in groups on the docks.

Moving to another country did not make much difference to me then. The trauma was about leaving our home without any money. At that moment, India and Pakistan were mere words. My sister would just lie on Mummy’s lap, holding on to her ‘pallu’. She did not understand as much as I did. The fear of the unknown… the insecurity of homelessness… the discomfiture in imposing upon our maternal uncle’s hospitality.

Dad went to Delhi in search of a job and was able to get one on the basis of his experience in government service. He joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in Delhi. After spending about a month in Bombay, we travelled by train to Delhi where we fared better than most refugees, anchored as we were in a modest home in Dev Nagar.

I was admitted to Lady Irwin School in Delhi, along with Indu, while Gul still had a year before getting into school.

Karachi to Delhi was a long haul but Mummy would take us back to our Karachi days by making ‘maanis’5 and serving them to us piping hot. On winter nights we would eat in the kitchen for warmth, all of us sitting together on a ‘manjaa’ (cot).

Our parents were able to provide us a simple and comfortable life. They left no room for sadness in our life, instilling in us plenty of confidence and a fair degree of optimism that life was going to be pretty much alright.

Thanks to Mum’s thrift and diligence, we were never wanting for anything.

We were in Delhi from 1947 to 1957, when I finished my graduation in Maths Hons from Miranda House. Dad retired in 1957 from the Ministry, and we left for Bombay. Our own lives as adults were about to begin.

Shamlu Dudeja lives in Kolkata. She is the founder of Malike Kantha Collection & Trading that has helped the revival of a form of embroidery traditionally done by women that enabled the generation of income for them. She is also the founder of Calcutta Foundation that works with deprived children.

Footnotes

- Meaning the great leader

- The Nehru jacket is a hip-length tailored coat for men or women, with a mandarin coat, and with its front modelled on the Indian achkan or sherwani, a garment worn by Jawaharlal Nehru, the Prime Minister of India from 1947 to 1964.(Wikipedia)

- The sacred text of the Sikhs

- sage

- Flat chapattis made from wheat flour kneaded with a little ‘ghee’ and water. Balls of the dough are rolled, smeared with some ‘ghee’, gathered into a ball and re-rolled before cooking and puffing on the griddle

Very interesting story.

Very nice reading of a first hand experience of the horrors of partition.