Smile – and the world smiles with you. Grieve – and you grieve alone.

These had been the words I had somehow memorized in my childhood when I first went to school. It was a school run by Catholic nuns. Those words stuck out precisely because they did not fit the pattern of grieving that I had grown up with in my large extended family in Bengal. There, every death and every birth occasioned a collective gathering, fasting and then feasting together. Grieving alone was a relatively new and adult experience for me.

It occurred the first time in August 1982, when I lost my beloved paternal grandmother, Nirmala Devi. I had been a mere 20-year-old, writing my final BA exams in Delhi University. Just a year before that, while studying for my History honors degree, I had discovered a method called Oral History. It involved asking informed but open-ended questions to someone and recording their answers. One summer night, lying on adjacent cots, I turned a tape-recorder on, and began to ask her questions about her past. That is how I learned that my grandmother had been only 9 years old when she had been married to my grandfather, the eldest of 4 brothers. I also learned that her parents-in-law had treated her compassionately as a child bride: they had let her sleep with them because she knew no better! That night she had laughed and explained that it was perhaps the reason that she had borne her first child only when she was 17. That the child had been so beautiful, the household had named her Durga after the deity. But she had died within a year. There had been another daughter – the youngest – called Joyee, who had grown to adulthood but was drowned in the local pond overcome by an epileptic fit as she was cleaning the large brass utensils used in daily worship. Eventually seven of her sons and two daughters survived. My father was the oldest and she always referred to him as Shelu.

That night, she had also told me that my grandfather had worked in the colonial government’s audit department. As a government servant’s wife, she had lived in Shimla some summers too, and have even visited Lahore a couple of times. But by 1946, recognizing that the rest of their families living in Khulna might fare better in Kolkata, they had begun to save to rent a larger house in that city. So when the Partition occurred in 1947, a move that he had contemplated merely as an education necessity for the children became a permanent social upheaval for the entire family. The 4 brothers, their wives, children and many dependents and servants moved from Khulna to a place called Habra, in north 24-parganas, Bengal. Today it is bustling little urban township on a train line. Back then, it was a marshland that had to be drained. According to my grandmother’s story, my grandfather had drained portions of that land and planted tropical fruit trees there while my grandmother held an umbrella over his head to shade him from the sun. Though his firstborn son was nowhere near getting married, my grandfather was confident that ‘Shelu-Dilu’s children’ would soon arrive and relish the fruit. Dilu was the eldest son of the second grandfather.

As Shelu’s firstborn, I was obviously much petted and fussed over. There were many stories told by my uncles about the month of my birth, an acutely hot May. My baby back erupted in boils so that I could not be laid down on my back. My grandmother lulled me to sleep on her own bared bosom, my infant belly resting on hers the whole night. When I learned to walk, I waddled about with her hips. And when I learned to cook, I learned chefs’ tricks from her. I had even gifted my tape-recording from the summer before, my most cherished possession, to my father because I knew it would comfort him – and perhaps impress on him the worth of a History degree! Perhaps I did too good a job of impressing my uncles of my academic worthiness. For when my grandmother died in August 1982, nobody disturbed me in Delhi. Writing my exams, I developed a tiny muscle for grieving alone.

That muscle was exercised again a decade later, when I left for higher studies in England, and the sole unmarried uncle also died suddenly in Kolkata. He was called Bhalo Kaku (Good Uncle) for very good reason. All children had a special place in his heart, beginning with his baby brothers and sisters and then extending down to us in the next generation. His twin fascinations for both family and photography made him acquire a box camera one day – an amazing feat in a post-partition refugee family still struggling to get back on its feet! And we became his adoring subjects. We soon became his supplicants. For instance, at the age of 6, when I first went to school and saw a novel sight – of an adult woman wearing pink lipstick and high-heeled shoes – I asked my parents to buy me the same things. My parents were cold to such demands. But not my Bhalo Kaku. He bought me my pink lipstick – and then went on to buy me my first watch, my first silk sari (a dashing magenta with a thin purple border), my first cigarette (because it had to be the best! though I was taught to hold my alcohol by my father, bless him). He had even saved up 300 dollars to give me for my first international trip. And so when he died the minute I left the country, it seemed like a devastating betrayal of our lifelong friendship. Who would I write to about my first snowfall in London?

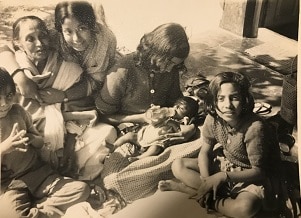

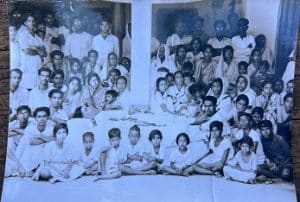

Grieving alone, I soon realized is also an inheritance of sorts. It can pass from father to daughter unbidden. Though in 2018, I managed to reach my father’s bedside before he breathed his last, I realized immediately afterwards that I had inherited his solitary experience of grief. I was ransacking his cupboards, trunks and suitcases for photo-albums, clothes and odd bits and pieces of him that I could carry with me to the USA. It was then that I came face-to-face with a grainy black-and-white photograph of a dead man lying on a cot, surrounded by about 80 people, old and young. When I peered at the photograph, I realized that the dead man in the picture was my paternal grandfather. Sitting by him with the vermilion on her forehead smudged all over her forehead was my youthful grandmother, with large lustrous eyes, and jet black hair. Seated and standing around them were all the young people I was to call granduncle, third grandfather, uncles and aunts. The third and fourth grandfather’s children were way younger than my father and his brothers. Yet, even as children, they were identifiable in that black-and-white picture. But there was no face there that resembled my father’s.

That was when I knew. This photograph had been taken for my absent father, in whose belongings I had found it. It dated to 1956, when my father was on a far outpost somewhere. Convention decreed that as the eldest son, he light the fire that would consume my grandfather’s earthly frame. But my father had taken on the hardest part of this conventional role – of feeding his parents’ vast family of refugee-kinsmen and women. A recently graduated medical student in pitiless post-partition conditions, he had taken up the only job he could get. It was a short commission service in the newly partitioned Indian army. He was assigned to the medical corps, and posted to some remote border post from where he could not descend in a hurry to attend his father’s cremation.

Recognizing that my unmarried father and I had had the identical experience of grieving for loved ones from a distance was oddly comforting. He had used his grief to nurse others, to live humbly so that he could send his earnings home for all the other siblings to survive with dignity. If my father had survived grieving alone, so would I. My resolution was sorely tested then in 2021-22 when one after another, I lost my young sister-in-law, a married-in aunt, my youngest uncles from that long-ago photograph, and my most beloved maternal aunt. Yet what I mourned was not that I would not see them again, but that I would not feel all their love, generosity, their taste in beautiful things and sounds, for laughter, their compassion. It felt like all the certitudes of my life had dissolved into some irrecoverable void.

That is when I remembered the prayer-rug that I had carried about with me for three decades or more. My paternal grandmother stitched it out of thread and wool patiently taken from discarded saris and sweaters. She began this somewhere in her 20s and finished it sometime in her 40s. Having become a refugee meanwhile, she never got to use it. Especially after she was widowed. The prayer rug was put away in a wooden chest kept under a huge bed, along with all the prayer vessels and utensils of use in a vast household. Naturally, mice and other friends found their way to the chest, and nibbled many parts of it. Then my mother entered that household as a bride. One day, asked to drag out something stored in the wooden chest, she found the rug. And lamenting that nobody had cared for her mother-in-law’s hard labor, she patiently restored the chewed through bits. With fresh thread. While raising a bunch of us. When she had finished, she told my grandmother who was so moved she told my mother to use it. But my mother could never bring herself to sit on work lovingly created by an elder’s hands. It was folded away again, and carried about all over the country for another decade or so. Till one day, looking to borrow a sari from Ma, I stumbled on this rug. And took it away to Delhi. With the first wages of my first job, I had that bound. Sadly, that glass too broke in one of my many moves across the oceans. The wooden frame too broke. But the rug, now stuck to a board, persevered.

On the first day of the New Year, I posted the picture of this rug on Facebook blessing my friends and family to “be that rug”. The latter responded in ways that showed that the pandemic had also opened their eyes and hearts in new ways. All of them spoke about the rich tapestry of love that had tied one generation to another. But most of all they responded to my blessing on all of them to “be that rug”. In English, women are scorned as “doormats” if they endure suffering and grief silently. But no Englishman had seen my grandmother’s rug, created from discarded material, loved by two generations of women after her, who repaired it, restored it, renewed it and reframed it. When I blessed my friends that they would be that rug, I was not wishing on them a life of inert silence. What I wished was that they would feel the love of many generations that would repair their wounds, and wipe their tears; like the rug, they would not merely survive the disasters of our lifetimes, but be renewed and restored repeatedly. And finally, I wished that just as that rug had remained an object of beauty in my life, their lives would bring a smile to others. For if my grandparents’ – and parents’ – stories had taught me anything, it was that love and mutual compassion could outlast grief and loss – and in helping others recover, we could all heal ourselves. Even if it was one stitch at a time. Or one object at a time.

Indrani Chatterjee was born in a military hospital in Kolkata and went to school in different towns of the country. Every summer she and her brother were sent back to Habra to live with their cousins in the extended family centered on her widowed grandmother. So she learned to read, write and speak Bangla, as well as the skills of coexisting with people from different generations, educational and economic backgrounds. She currently teaches Indian history and lives in Austin, USA, with another historian for a husband, and loves listening to music, photography, and cooking.