I am flooded with memories of the original narrator of this story as I sit down to write. I can clearly see raindrops splashing into the front porch of an old three-storied house of Kolkata, us chatting and enjoying the rain-soaked view outside, along with tea, chire bhaja [note] flattened rice which is often roasted dry [/note] or some other home-made snack.

The story is about the narrator’s aunts, Sweet Mashi, Mini Mashi and Neru Mashi. The narrator, in turn, was an aunt, or ‘Mashi’ of mine, who passed this down to me about 16 years ago. She was my dear friend Aveek’s mother, Sreela Sen or ‘Mashima Sen,’ as she was known among her son’s friends. She knew a lot of people, had a large and diverse circle of friends and had a wonderful flair for telling stories.

While researching the early history of the Sakhawat Memorial School founded by the pioneering educationist and writer Rokeya Sakhawat Hossein in Calcutta in 1911, I had the opportunity to talk to some of its alumni from the 1930s and 40s. Several of them from Dhaka and Kolkata were still around in 2010-11. Sreela Sen or Mashima was one such alumna. After the Partition of India, Sreela’s family had to migrate to Kolkata from Dinajpur town which had suddenly become part of East Pakistan in 1947 and now belongs to Bangladesh. On coming to Kolkata, she took admission at the Sakhawat Memorial School in 1948.

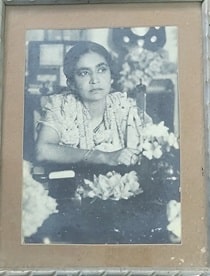

The ninth-grade student was often ill those days due to the psychological trauma of Partition. That year, veteran educator Suhasini Biswas, or Sreela’s Neru Mashi, got transferred from Dhaka to Kolkata’s Sakhawat Memorial School as the new Headmistress. Suhasini had already earned respect and renown for her three-decade-long headship at the Faizunnisa Girl’s School in Kumilla, which is now a district town of Bangladesh.

So, how did Neru Mashi become one of Sreela’s beloved aunts? Sreela Sen was a member of the Brahmo Samaj. Her mother Shantiprabha Nag (nicknamed Annie) was a brilliant student of Mathematics and a renowned school teacher in early twentieth-century Bengal. One of Shantiprabha’s many illustrious works was to build and nurture the Dinajpur Girls’ High School since the early 1930s, with the help of her husband, Nirmal Chandra Nag. Shantiprabha’s husband had moved from Dhaka to Dinajpur to teach English at the new school where his wife was located. According to Sreela, her father Nirmal Chandra’s ‘masculinity’ was not even remotely injured while working in the same school where his wife was the Headmistress. The story of Shantiprabha and Nirmal Chandra’s camaraderie is also remarkable. But let us shelve that story for another day.

That Sreela’s mother Shantiprabha would have several friends working in the field of education all around the undivided twentieth-century Bengal isn’t surprising. Two such friends were Surama Biswas and her younger sister, Suhasini Biswas. These Bengali Christian educators were close to Shantiprabha’s entire family. Thus, they were Sreela’s Sweet Mashi and Neru Mashi, whom she thought of as her ‘role models.’ Shantiprabha’s younger sister Suprabha Dasgupta, or Mini, used to be Mini Mashi for Sreela.

Sweet Mashi, Mini Mashi, and Neru Mashi were well-known in the sphere of school education. Suprabha Dasgupta or Mini Mashi was the Headmistress of Dr. Khastagir Girls’ School in Chittagong. She had joined the school as an Assistant Headmistress in the 1920s, while Surama Biswas or Sweet Mashi had been in charge. Suprabha, of course, was already well-acquainted with her older sister Shantiprabha’s dear friend Surama. But Surama and Suprabha’s professional collaboration and close friendship began during the Chittagong period. Their school became known far and wide because of Surama-Suphrabha’s admirable efforts and their friendship too lasted lifelong. The bond didn’t slacken even as a few years later Surama moved to Dhaka to take on the new role of the Inspector of Schools, Dhaka Division.

Surama was allotted a government bungalow in Ramna area of Dhaka and that became Sreela’s second home. Sreela’s parental home that her mother Shantiprabha ran at Rankin Street in old Dhaka had been home to Surama and Suhasini as well, so much so that a few years later, after being released from Japan’s Fukushima prisoners’ camp in December 1945, Suhasini spent most of 1946–47 at Rankin Street to recover from failing health. She had initially returned to her sister Surama’s house in Ramna. However, since Surama had to frequently travel outside Dhaka for school inspections, Suhasini moved to Shantiprabha’s house to recuperate.

According to Sreela, Suhasini or Neru Mashi had returned severely malnourished and weak. All her teeth had fallen off and her skin was burnt black. For three years, she had endured starvation and torture at the prisoners’ camp, which included walking on ice slabs and standing in the scorching heat for hours.

How did Suhasini, the Headmistress of Faizunnisa Girls’ School, fall into such a fate? In 1941, Suhasini had received an opportunity to go to Australia, sponsored by the Australian Baptist Mission. Despite the Second World War, she fearlessly went abroad and after finishing her work in Australia, boarded a ship to return home in 1942. But on its way home, the ship S.S. Nanking, was attacked by the Japanese and all passengers of the ship became prisoners of war. That’s how she ended up in Fukushima.[note] In the outskirts of Fukushima, a Catholic convent was converted to an internment camp, notorious for the poor treatment of prisoners[/note]

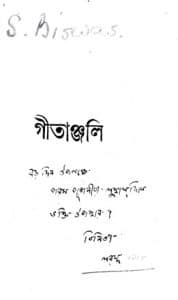

Suhasini always kept a copy of Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali with her. She deceived the Japanese camp authorities by claiming that the book was a Bengali edition of the Bible. During that time of deep crisis, she clung to Gitanjali and chronicled her thoughts next to the songs. Suhasini returned home after the end of the war, but could barely recuperate over the next two years, when India was partitioned.

In 1948, Suprabha too had to leave her beloved Chittagong and Dr. Khastagir Girls’ School. She was transferred to West Bengal of the newly-independent India as the Principal of Jalpaiguri Girls’ High School. Surama too migrated from Dhaka and joined the Refugee Rehabilitation Department of the West Bengal government in Kolkata. However, throughout their ordeals, Sreela’s Sweet Mashi, Mini Mashi, and Neru Mashi’s friendship stayed strong. They became closer than ever after their retirement—especially Surama and Suprabha.

The aunts hailed from large families with many brothers and sisters, nephews and nieces, grandchildren and other relations, with whom they were in regular touch. But even outside the patriarchal family structures, these independent women challenged stereotypes and believed in creating a different kind of family and collectivity. In the early 1950s, Surama and Suprabha built a home in the Purba Pally area of Santiniketan, the now bustling University town where Rabindranath Tagore had founded an alternative school and the Visva Bharati University.

Surama and Suprabha’s house was in a desolate area bordering the railway line towards the east of Santiniketan, which was once a secluded place surrounded by undulating geological formations called khoai caused by gully erosion along the banks of the Kopai river in this region of laterite soil. They lived there mostly together from 1953 to the early 1970s. Many such individuals leading unconventional lives and wanting to be away from the madding crowd, chose to live in Santiniketan those days. Surama used to divide her time between Santiniketan and her father’s house at Mullen Street in Kolkata. She passed away in 1972 and shortly afterwards Suprabha was forced to move to her sister’s house in Kolkata after suffering from a stroke and becoming bedridden. Suprabha died in 1973.

My college-going Mashima, Sreela, often visited her aunts in Santiniketan. Her Sweet Mashi and Mini Mashi had completely different dispositions. Sweet Mashi loved to aesthetically decorate all the rooms in their new house and had grown a garden all by herself. She was also a wonderful cook and would create novel dishes every day. Sweet Mashi had no interest in going to the church on Sundays. Instead, all her morning was spent on doing things like preparing a roast chicken for a sumptuous lunch. Mini Mashi, on the other hand, would not be seen anywhere near the kitchen and spent her days reading. Whenever Sweet Mashi left for Kolkata, Mini Mashi would tell her niece, “How about we make do with rice-puffs, milk, and banana today?”

It’s not difficult to imagine Sweet Mashi as the role model of the aesthetic and culinary expert Sreela. But what was Suhasini, or Neru Mashi a role model for? “For her grit, determination and zest for life,” Sreela had told me. At the end of the war, when all the released prisoners were desperate to return home, Suhasini Biswas had reportedly told the Japanese, “I’m yet to see cherry blossoms even after living in your country for three years! I’m not going anywhere until I see some!”

Acknowledgement: This was first published in Bengali as one of the pieces of my fortnightly column ‘Doshor’ (Of Friends and Comrades) in August 2024 in the digital platform robbar.in

I wish to thank Shambhobi Ghosh, my young friend and a gifted writer, for working with me to produce this modified English version for www.pastconnect.net

Photo credits: Jayati Gupta, Sunipa Basu, Sarmistha Das

Sarmistha Dutta Gupta is a Kolkata-based independent researcher, bilingual writer and curator. Her books include The Jallianwala Bagh Journals: Political Lives of Memory (Jadavpur University Press, 2024) and Identities and Histories. Women’s Writing and Politics in Bengal (Stree, 2010). She is a columnist of the editorial pages of Anandabazar Patrika and Sangbad Pratidin’s digital platform robbar.in