I was around 9 or 10 when I first learnt that my mother’s thakurma (paternal grandmother) hailed from Assam, not Bengal as I had assumed, and that she shared a name with my mother’s maternal grandmother – Swarnalata. That information disappeared into the recesses of my mind. At that age, I was not too interested in my lineage. I was definitely not curious about ancestors who had died even before my parents were born. Over the years, I picked up snippets of information about long-departed progenitors, from random conversations among family members. Nothing out of the ordinary, nothing to pique my interest. What I learnt about Swarnalata was that she had been widowed with two daughters, one of whom died in childhood, that she remarried and had six more children – four sons and two daughters, the eldest of whom was my maternal grandfather – Prodosh (Tunu). Widow remarriage was an accepted fact amongst Brahmos and I was not surprised, not realising that this particular one took place in the 19th century, when the practice was still frowned upon. That she was from Assam and not Bengal again did not surprise me as inter-state, inter-community marriages were not rare in our family.

I did not know anything more than this about Swarnalata. I don’t think anybody else, in my generation or the previous one, knew very much either. My grandfather, Prodosh (Dadubhai, to his grandchildren), was not a talkative soul and except for lamenting the fact that his mother had not married Rabindranath Tagore, thanks to Debendranath Tagore’s1 rigidity, he did not share any other nugget of information about her. His siblings too did not talk about their parents or their many, many achievements. So, as in the case of Khirode Chandra Roy Chowdhury, Dadubhai’s father2, we have very little personal details.

Swarnalata remained an unknown entity to us till a cousin found and read an English translation of Tilottama Misra’s3 book – “Swarnalata”. The book, a blend of history, fact and fiction got some of us in the family sufficiently interested to try and find out more about this fascinating, progressive ancestor of ours, who was one of the first few women writers in Assam, and one of the three who advocated women’s education and argued in favour of women’s emancipation in 19th Century Assam. As I delved into Swarnalata’s life, I realised that her parents – Gunabhiram and Bishnupriya – were the original trail-blazers of the time and of our family. They set the stage for their daughter and inspired and guided her to make a mark on the social and literary scene in Assam.

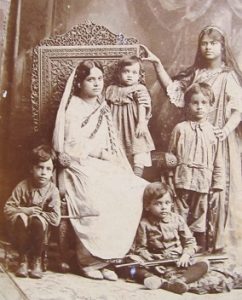

Swarnalata was the eldest child and the only daughter of Gunabhiram Baruah and Bishnupriya Devi. She had three younger brothers – Karunabhiram, Kamalabhiram and Jnanadabhiram. She was a spirited woman with a strong personality, tremendous self confidence and immense faith in the Almighty. Hers was not an easy life. She had to face many hardships, battle many storms and take on a lot of family and financial responsibilities from a very young age. Her life was dogged by personal tragedies almost on a continuous basis. But she steered her family through tough times, managed property, finances and court cases and overcame family and financial problems with immense fortitude and efficiency. After her marriage to Khirode Chandra, she was completely immersed in family and household duties. Her literary efforts took a back seat, more so when Khirode passed away leaving her to bring up 6 children – all minors, with the eldest being just 16 years old. Yet, thanks to her guidance they were all highly educated and well established in life.

Swarnalata’s character was primarily shaped by the teachings and ideals of her father Gunabhiram Baruah, the courage of and the example set by her mother, Bishnupriya and by the environment and the times that she grew up in. So before talking about her, I will begin with what I learnt about her parents – Bishnupriya Devi and Gunabhiram Baruah.

II

Born in Upper Assam in 1834, Gunabhiram Baruah joined the government service, rising to the rank of a First class Magistrate, duly feted by the colonial state with a honorific title, Rai Bahadur.

However, it was his contribution in the field of Assamese literature and culture that he is best known for. One of the earliest converts to Brahmoism in 1869, he started the Brahmo Samaj together with Padmahash Goswami, in Nagaon from where the religious reform movement spread to other parts of Assam. In keeping with the principles of the Brahmo Samaj, Gunabhiram campaigned against polygamy and child marriage and advocated widow remarriage. After the death of his first wife, he married Bishnupriya Devi, who was a widow with two young daughters who were already married. The marriage created quite furore and the couple had to face social ostracism.

Gunabhiram turned to writing and wrote widely, contributing to the development of Assamese literature as well as to women’s cause-their education and emancipation. He started in 1885, a monthly literary journal, Assam Bondhu which however was short lived. He encouraged Bishnupriya to write and contribute to magazines and newspapers.

III

Swarnalata, brought up by such progressive, liberal-minded parents, naturally gravitated towards social issues, especially with regards to women. There weren’t any proper schools for girls in Assam when Swarnalata was growing up – in fact, girls from “good homes and families” were not encouraged to study. They were brought up to become good wives and mothers, and married off at a very tender age. Not so in Swarnalata’s case – Gunabhiram initially had her tutored at home.

There was a Christian Missionary School in Nagaon where Gunabhiram often attended special programs accompanied by Swarnalata. He admitted his daughter to this school only to realise soon that the school authorities were more inclined towards propagating Christianity than in educating women. So, he decided to send Swarnalata to Calcutta to study. It was a difficult decision for him and Bishnupriya and it was not easy for the little girl either. But he did not wish to compromise on her education. So 9 year old Swarnalata was sent to Calcutta and enrolled in Bethune School4.

In those days, the journey from Nagaon to Calcutta took 10-12 days – by bullock-cart from home, then by boat/ferry across the Brahmaputra followed by the train to Calcutta and finally by bus or horse buggy to the final destination in Calcutta – it was an ordeal. In addition, the city must have been very frightening for the little girl. She did not know the language Bengali, she knew nothing about Bengal and the family had no relatives in Calcutta. Gunabhiram’s youngest son, Jnanodabhiram mentions this in his autobiography, Mor Katha5, commenting on the courage of his parents in taking this difficult step. Swarnalata spent some time in the school hostel and then moved to Manicktola Street where Bishnupriya rented a house for sometime. Swarnalata was in Calcutta for a total of 7 years. At that time, progressive Brahmo families in Calcutta had started sending their daughters to school. But to send a 9 year old all the way from Assam to study in Calcutta was quite revolutionary. Swarnalata was, in fact, the first Assamese girl to be sent outside the province to study.

Gunabhiram had many friends in Calcutta among the educated, progressive and intellectuals of that time – Ananda Mohan Bose6, Sir Jagdish Chandra Bose7, Umesh Chandra Dutta8, Durga Mohan Das9, Kadambini Ganguly10, and others. A similar environment existed in Nagaon too where Gunabhiram’s circle of friends included intellectual stalwarts and cultural icons.

There was thus an atmosphere of culture, radical ideas, and intellectual thought in the Baruah household, both in Calcutta and at Bilwa Kutir, their residence in Nagaon. This gathering of educated, high thinking, visionary individuals engaged in discussions and debates on a variety of issues, social and political. Swarnalata was encouraged by her father to be present at these sessions and take part in and contribute to the conversations, thus exposing her to progressive thought and ideas.

On returning to Nagaon from Calcutta, Swarnalata helped her father in his literary pursuits – she was tasked to dispatch Assam Bondhu to readers, by writing the addresses, fixing the stamps and arranging to have them delivered. She also contributed articles to this and other Assamese journals like Jonaki and Bijuli. Novelist Chitra Deb, writes in her Women of the Tagore Household, “Exceptionally beautiful, Swarnalata was a student of Bethune School and later became a well-known writer. She is also acknowledged as the first woman journalist.”

Swarnalata was a major contributor to the literary world of Assam. Nalinidhar Bhattacharya, a poet and literary critic from Assam, regarded Swarnalata a pioneer in the field of women’s emancipation and women’s education in Assam. In the words of writer Hem Bora – Swarnalata was the main woman writer of the Jonaki age. In Swarnalata’s writings the mentality of the Assamese women of the age have been reflected. Her articles have a distinguished place in the new trend of Assamese prose writing. The Jonaki age(1873-1881) was the era of romanticism and modernism influenced by western thought, in Assamese literature. It also saw the entry of many women writers. Swarnalata was also the first Assamese woman to use a pen name (Hemlata Devi) for some of her articles in Jonaki. Her first article was written when she was still in school , at the age of 14. While we do not know for certain, in all probability, most of her writing was accomplished in her teens, before her marriage.

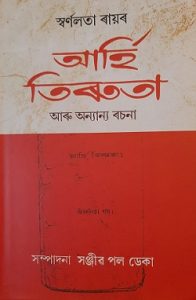

The only published book to her credit is Arhi Tiruta (Exemplary Woman). It was published in 1919 after Khirode Chandra’s death. This book is seen as an important contribution to Assamese literature, as the first collection of biographies of 9 singular women who did not conform, and were not afraid to walk the path less traveled, who lived life on their terms with determination and dedication. Her selection of exemplary women include Hindu, Muslim and Christian women from different walks of life and from different regions of India and other countries. As such her book stands apart from other biographies and books about women in both Assamese and Bengali literature in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some of the articles in Arhi Tiruta had been published earlier in Assam Bondhu, Jonaki and Bijuli.

In the introduction to Arhi Tiruta, Swarnalata wrote that she had put together this book in her spare time from household responsibilities and she hoped that it would motivate her Assamese readers. Post her move away from Assam, this was her first attempt at writing in Assamese.

IV

Sometime in 1883, Swarnalata visited the Tagore mansion with her father to attend a function. A match was proposed between her and Rabindranath at that time. The poet was agreeable to the idea but his father Maharshi Debendranath Tagore turned down the proposal when he learnt that Swarnalata’s mother had been a widow before marrying Gunabhiram. Jnanadabhiram says in his autobiography – ‘The will of God ! Borodidi’s11 marriage to Kobi Guru Rabindranath did not take place’. The brother was quite distressed at this rejection of his sister. What Swarnalata’s feelings were on this, remain unknown.

In the face of this rejection, Gunabhiram and Bishnupriya despaired of finding a suitable upper class Assamese husband for their daughter. But they need not have worried. Swarnalata was married to Dr Nando Kumar Ray in May 1887, at the age of 16. The marriage was held in Nagaon where Gunirabhiram was stationed. Nando Kumar was one of five brothers belonging to a highly educated Dacca based family. All the siblings were graduates and more (a rare phenomenon in those days). Nando Kumar studied medicine in India and then in Edinburgh as a recipient of the Gilchrist Scholarship. He came back to India after completing his studies in Edinburgh.

A smart, intelligent, lively, western-educated, “foreign”-returned young man, especially a doctor, was a rarity in Assam at that time. Gunabhiram and Bishnupriya were overjoyed with this alliance. Nando Kumar and Swarnalata’s marriage was seen as a “raj-jotok” – a match made in heaven. Nando Kumar worked with the Railways for a while but was asked to leave on false grounds after being wrongfully accused. He then moved to Kathmandu to serve as the physician to the King of Nepal. Very soon he became a great favourite of the King’s. As a result he incurred the displeasure and hostility of the Ranas (Ministers), who were in actuality the rulers of the mountain kingdom with the King being just a figurehead. They succeeded in poisoning the King’s mind against him. One evening while visiting a friend, he was issued a royal “farman’ to leave the country and was escorted by armed guards to the border of Nepal and India, on a moment’s notice – he was not even allowed to go home and pick up any of his possessions.

He returned to Calcutta and practised medicine while staying with his elder brother, Rajani Nath. But the fates were against him and his family. On March 31st, 1890 he passed away, leaving behind 19-year old Swarnalata and two little girls – Khuki and Chhoto (Lolita). Thus began Swarnalata’s struggles and hardships – emotional, legal and physical.

On receiving news of his son-in-law’s death, Gunabhiram shifted to Calcutta permanently. Swarnalata moved back to her parents’. Just when the family was beginning to settle into some sort of rhythm, Bishnupriya passed away on March 26th, 1892 and Swarnalata had to take over all her household duties. Her father was in no state of mind to take care of anything. But this was not the end of the family’s tragedies.

Gunabhiram’s eldest son, Karunabhiram was a couple of years younger to Swarnalata. He was the founder and editor of the first children’s magazine in the Assamese language – Lora Bondhu. The name of the magazine is believed to have been inspired by the English children’s magazine – The Boy’s Own Paper. It was published from Nagaon – the first issue was published in 1886. Unfortunately it was discontinued in 1888 after just four issues. Karunabhiram was a bright student and Swarnalata entertained hopes that he would join the Indian Civil Services. But that was not to be. He fell ill even before the results of his entrance examinations to Presidency College, Calcutta were declared. The doctors suggested shifting him to a drier climate, away from the humidity of Calcutta. Gunabhiram shifted to Madhupur, Bihar with him but Karuna did not recover- he succumbed to Kalajor12 on July 12,1893.

The pain and agony of losing so many loved ones in such a short time proved too much for Gunabhiram and he passed away on March 25th, 1894 – less than a year after his son.

Swarnalata realised that she could not give way to despair. Dependent on her, were four children – her two daughters and two younger brothers. Help came from stalwarts of the Brahmo Samaj – Ananda Mohan Bose, Durga Mohan Das, Dwarkanath Ganguly, Lakshmikant Bezbaruah, and her brother in law Rajani Nath Ray. They organised her stay at the Brahmo Girls School Hostel with her daughters. Her brothers Kamalabhiram and Jnanodabhiram were sent to the Brahmo Boys School Hostel.

Swarnalata was not given time to grieve for her brother (Karuna) or her father. Hordes of relatives – near and far – descended upon her like vultures to do her out of her rights. Gunabhiram was a wealthy, propertied man and by law his children were the heirs to what he had. The contention of the relatives was that the children were illegitimate, their mother’s marriage was not valid as she was a widow and hence they could not be legal heirs. Swarnalata was not one to accept such false allegations. She produced her parents’ marriage certificate in court, won the case and was appointed guardian of her brothers and trustee of her father’s property.

But tragedy reared its head again. On November 30th, 1894 Kamala, her second brother also died of kalajor. Khuki, her elder daughter died around this time. ( I could not locate any more details about either Kamalabhiram or Khuki). Rather than get her down, these incidents only served to make Swarnalata stronger, more determined, more resilient and more hardworking. Worried for Jnanodabhiram after the deaths of Kamala and Khuki, on the advice of friends and well-wishers, she took a decision to send him to England for higher studies. In London, Jnan studied Law, became a Barrister and was appointed the first Principal of Earle Law College – one of the oldest law colleges in India – which is now known as BRM Government Law College, Guwahati, the capital of Assam.

Jnanadabhiram became a well-known Assamese author and translator. He was married to Latika Tagore – the granddaughter of Dwijendranath, Rabindranath’s elder brother. In his memoirs, Mor Kotha , Jnanadabhiram says – “Strange are the ways of fate. The marriage of my elder sister to the Poet (Rabindranath Tagore) never took place. Yet Latika, the eldest daughter of Arunendranath and grand-daughter of the learned philosopher, Dwijendranath, was wedded to me on July 1, 1906. How opinions and views change ! This match was arranged by my elder sister, Swarnalata. Now many widow remarriages are taking place in the Tagore family.” Rajen Saikia, an Assamese researcher, author, critic and translator, writes about Jnanadabhiram’s marriage – ‘ By the standards of the age, it was an uncommon marriage relation and it serves as an index of social metamorphosis.’

V

On March 15th, 1899 Swarnalata married Khirode Chandra Roy Chowdhury, a well-known educator and scholar. Khirode Chandra was a widower, twenty years older than her and had seven children by his earlier marriage. In spite of the age difference, Khirode and Swarnalata led a happy married life for seventeen years. They had six children – Prodosh (Tunu), Prodyot (Munu), Pronob (Dhunu), Pronod (Runu), Ila and Bela, whom she brought up on her own after Khirode Chandra’s death in 1916.

Khirode Chandra had taught at various places before moving to and finally settling down in Cuttack, Orissa. Apart from being an educator, Khirode Chandra’s interest in literature and journalism led him to write and then start his own printing press that published two newspapers – the English “Star of Utkal” and the Bengali “Mrinmoyee”. What is surprising, however, is that Swarnalata does not appear to have been involved with any of her husband’s literary efforts. She seemed to have stopped writing, altogether. Even though Aparna Mahanta, academic, activist, author says about Swarnalata, “remarried and moved to Cuttack and her link to Assamese literature was lost,” Arhi Tiruta, written and published in 1919, remains a testimony to the contrary.

There are three incidents that I will relate from Swarnalata’s life in Cuttack ( courtesy Rina Nandy and my mother Indrani Paul, both granddaughters of Swarnalata and Khirode Chandra) that throw light on the kind of person she was. Once when she was returning home in her vehicle (not certain if it was a horse-carriage or a car or some other form of transport) there was a massive traffic snarl-up on the road. She waited a while and when she saw that the traffic police was completely unable to sort out the situation, she calmly alighted from her vehicle and directed the traffic till order reigned once more.

Another time, she was informed by her second son, who looked after the family finances, that money was short – there wasn’t enough for food and other provisions for the next day. She said in her stoic way, let’s see what the Almighty has in store for us. The morrow brought news of some money that was due to them and the immediate problem was resolved. Her faith and calm in the face of any kind of trouble – big or small – was admirable.

The third incident – Khirode Chandra was visiting a famine affected village in Orissa. A man wanted to sell him, his two daughters for a sum of Rs 6/- as he could not feed them. Khirode brought the girls home. One died soon after; the other, Jamuna, was brought up by Swarnalata with a lot of love and care; she was treated as a daughter of the house. When the girl was around 15-16 years old she eloped. There was no news of her till a few months later when she landed up, pregnant, destitute and sick. Swarnalata took her in but anticipating trouble from the neighbours for this act, took Jamuna to a nearby Church, where the priest initiated her into Christianity and organised her accommodation. Her daughter, Jahnavi, was brought up in the Church and later married a youth working there. The two together took care of Jamuna the rest of her life. In the Roy Chowdhury household, Jamuna was the surrogate elder sister, the ‘ Boro Nonod”13 to the wives of her four brothers. Mother and daughter were part of every celebration in the family. Not only did Swarnalata save Jamuna from dishonour, she also helped her build a life for herself and her child and included her in the family as a much loved daughter.

Swarnalata died in Cuttack in 1932 – probably of cancer, though it was not diagnosed as such at the time. She was as much an exceptional woman, as those she wrote about in Arhi Tiruta – far ahead of her times. Inspite of not having graced the literary scene for a very long time, interest in her works and in her life appears to have a life of its own. In 2013, a damaged copy of Arhi Tiruti was discovered by Sanjib Pol Deka, an Assamese author and a Professor in the Assamese Department at Dibrugarh University, Assam, in an old almirah in a library in Barpeta in Assam. The last few pages were missing. Deka had the book scanned and reprinted in 2019, on the 100th anniversary of its initial publication to revive interest in one of Assam’s early women writers. Tilottama Misra wrote a partially-fictionalised account of her life. Discussions about her contribution to Assamese literature still abound in academic and literary circles.

Before I end, a couple of interesting facts about her family: Her younger daughter from her first marriage – Chhoto (Lolita) was married to Prafullo Chandra, Khirode Chandra’s son from his earlier marriage. One of Chhoto’s six children was Amita Malik, India’s best known film and television critic.

Jnanadabhiram’s daughter Ira married Gitindranath Tagore and the eldest of their three daughters is Sharmila Tagore, well-known Indian film actor who was married to Mansur Ali Khan, the erstwhile Nawab of Pataudi. It’s interesting to know that we are related to royalty even though royalty does not know that we exist.14.

Sumita Sen divides her time between New Delhi and Kolkata.

Footnotes

- Rabindranath Tagore, the poet laureate from Bengal in eastern India and Debendranath, his father

- My story ‘Hermit and the Householder,’ published on Pastconnect, February,11 2020

- a writer, critic, and translator based in Assam, India

- The oldest school set up in Calcutta for girls

- My Story

- Social reformer, educationist, pioneer of the freedom movement, lawyer, religious leader of the Brahmo Samaj, India’s first Wrangler i.e a student who completed the third year of the Mathematical Tripos with first class honours at the Cambridge University

- Well-known scientist and writer of Bengali science fiction

- pioneer Brahmo, Principal of City College and a major contributor to women’s education

- Social reformer, Brahmo Samaj leader who contributed significantly to women’s emancipation and widow remarriage

- One of the first two graduates in the British Empire, one of the first two Indian female doctors with a degree in western medicine , the first practising Indian woman doctor

- Elder sister

- Also called Black fever

- Elder sister in law

- Swarnalata and Khirode Chandra’s youngest grand-daughter, the late Rina Nandy, sourced a lot of the information we now have on Swarnalata. There are some anecdotes that I picked up from my mother, who had heard them from her mother as Swarnalata died before my mother was born. Some of the other sources I accessed are Dipankar Banerjee’s ( a historian and Professor of History at Guwahati University) book, Brahmo Samaj and North East India, Sujata Chowdhury’s (ex-Principal of Brabourne College, Calcutta and Lolita’s daughter) autobiography, Mone Achhey and Swarnalata’s book Arhi Tiruta published a second time in 2019 through the efforts of Sanjib Pol Deka