A designed paper -green, a tad shade of blue- sticks to the cardboard cover, torn at the edges and frayed across, holding together lined pages surprisingly intact; the writing inside is in blue fountain pen, clear and unspoilt. That is what my Ma’s notebook looks like, one that has always been among her papers and writings, something familiar and part of our household and existence, evoking neither interest nor curiosity when we were growing up.

A designed paper -green, a tad shade of blue- sticks to the cardboard cover, torn at the edges and frayed across, holding together lined pages surprisingly intact; the writing inside is in blue fountain pen, clear and unspoilt. That is what my Ma’s notebook looks like, one that has always been among her papers and writings, something familiar and part of our household and existence, evoking neither interest nor curiosity when we were growing up.

The notebook has now turned into a curio as an object often does when it is among the few things remaining to reconstruct a faded past, conjecture, lore and imagination standing in for definite information. It is the only heirloom I possess from my grandmother, we called Dida-Prabhabati Guha (nee Dutt). More than forty years after her passing when Ma has withdrawn into her cocoon of forgetfulness, keeping out the pain of being left behind, I only have the notebook to tell me about Dida and her family and mine too. I regret having missed the opportunity of asking Dida about her growing up days; the excellent raconteur that she was, there would have been some fascinating accounts to record. Instead, here I am attempting to piece together a story of intertwined lives and differing fates under changing circumstances of individuals and nations.

I begin with a torn fragment of paper sticking out of the notebook with Ma’s hurried scribble in Bengali-kitchen, three generations (she retains the English word, generation in Bengali script). That it remained with Ma and that the first few pages were in a handwriting, I recognise as Dida’s, the three generations must mean her grandmother, her mother and herself. There is no date anywhere.

What it comprises is enough to conjure an image of five young girls and two boys, siblings in their teens sitting together to embark on a project which their Mother promises to help with. Sitting around a table or on a large four poster bed, their backs reclined on the wooden frame, they decide on putting together a collection of recipes in Bengali, everyone agreeing to contribute a chosen one. It was Prabhabati’s idea since she started it, the others joining in, each signing at the end of the recipe with initials in English. We read the names of Dida’s two younger sisters and two younger brothers. Three persons are mentioned by their relationships-Didi(older sister), Boudidi(older sister-in -law) and Ma. I have no means to ascertain if Didi was married and waiting to join her husband in his village home but the others were not which suggests that they were all in their teens for all girls had to be married well before they turned 20. Boudidi too must have been recently married because she was still living with the larger family of her husband. Prabhabati was next in line and the cookbook may have been in preparation for the new life she was contemplating. Was her marriage already fixed?

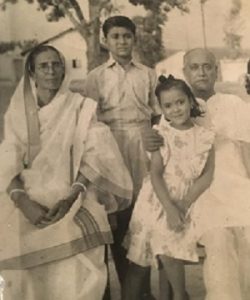

Prabhabati was married in 1912 or 1913, the year I calculate from Ma’s birth in 1925, twelve years after her parents were wedded. A year or two earlier, the 1910s, would make this green book more than a century old. Dida belonged to the Dutt family who lived in Dhaka, somewhere in the central part of the city where professional Hindu families resided. It was traditionally known as the family of lawyers who served the Nawab1. The house was a large one fronted by a gate, its pillars supporting lion heads, as Dida in her less fortunate days would recount with pride to her eldest granddaughter, my elder sister. Dida also recalled her daily trips to school in a phaeton. To me, the small, neat even letters in Bengali and a few in English were unmistakably Dida’s for I remember the yellow postcards that would unfailingly reach us with her blessings for the New Year and after the Pujas in autumn when traditionally regards and blessings were exchanged. For her favourite grandson, my elder brother who found it difficult to read Bengali in the running hand, she wrote Bengali in English script.

Back to unpacking the notebook, I start with what I have. I discover the names of other siblings- different handwritings and signatures belonging to Helen, Niharkana, Tejendra Kumar (TKD), R.K. Dutt and their Ma. It is a book of food- a total of around 50 recipes, 30 of which were carefully chosen and written down on pages which were numbered, indicating an order that may have been decided upon, the first 11 written by Dida. They were all selections of ‘special’ dishes, richer and more extravagant than the common daily fare, the ingredients exotic and expensive.

The first to appear were snacks, more elaborate than canapes, that a Bengali household would prepare to be had in the evening, well before dinner-sweets and savouries. The ones chosen are unusual like sweets made of yam, pulses, and fruits to be accompanied by more familiar Bengali patties stuffed with vegetables.

to be had in the evening, well before dinner-sweets and savouries. The ones chosen are unusual like sweets made of yam, pulses, and fruits to be accompanied by more familiar Bengali patties stuffed with vegetables.

There followed recipes for the main courses-of vegetables and pulses, of eggs, many dishes of meat and fish-the kalias and kormas, their origins in the kitchens of Persia and Arabia  transported to Bengal by migrant and itinerant trading and political communities. Local vegetables were used and Hindu customs adhered to which meant the meat was only goat’s, chicken being proscribed, with minimal use of garlic. I found only one dish, the Mughlai, sweet korma that required the meat to be marinated with garlic paste.

transported to Bengal by migrant and itinerant trading and political communities. Local vegetables were used and Hindu customs adhered to which meant the meat was only goat’s, chicken being proscribed, with minimal use of garlic. I found only one dish, the Mughlai, sweet korma that required the meat to be marinated with garlic paste.

Nothing indicates where these recipes were taken from, the language and the structure being comparable not uniform. Interesting was the use of measures that harked back to pre-metric custom2. The special Dal of Kashmiri origin was attributed to Boudidi, aubergine from Gujarat to Didi, none of whom seem to have written it. If they instructed someone, the similarity of language suggests the mediation of an author and some serious degree of collaboration. In a slightly slanting hand, TKD wrote down instructions for French fish fry, European cuisine finding little favour, except a German pudding, few jams and jellies of English origin and egg cutlets contributed by RK.D. Niharbala, the youngest among the siblings described the method of preparing a chutney made of sweetmeats. Here

custom2. The special Dal of Kashmiri origin was attributed to Boudidi, aubergine from Gujarat to Didi, none of whom seem to have written it. If they instructed someone, the similarity of language suggests the mediation of an author and some serious degree of collaboration. In a slightly slanting hand, TKD wrote down instructions for French fish fry, European cuisine finding little favour, except a German pudding, few jams and jellies of English origin and egg cutlets contributed by RK.D. Niharbala, the youngest among the siblings described the method of preparing a chutney made of sweetmeats. Here  their mother added three lines in a relatively colloquial language, suggesting that for a slight variation using a different sweet, the portion of sugar must be increased. She signs Ma in brackets, registering her presence and participation.

their mother added three lines in a relatively colloquial language, suggesting that for a slight variation using a different sweet, the portion of sugar must be increased. She signs Ma in brackets, registering her presence and participation.

The Mughlai kichdi, made of rice, lentils and meat with duck eggs, by Helen Dutt, was the richest, using an array of spices, nuts, raisins, yogurt, cooked in ghee, over slow fire and in a pot with the cover sealed and when done to be served with a sprinkling of rose water-very Nawabi indeed!

with the cover sealed and when done to be served with a sprinkling of rose water-very Nawabi indeed!

After a few more entries in bold, childish hand possibly Helen’s, the notebook remains with Dida, and the rest of the entries are by her on pages not marked, till she hands it to her daughter, Leena who thereafter inscribes it with her presence and changed circumstances.

Did the teenagers in their adult lives try any of the recipes out? Once the notebook is claimed entirely by Dida, the list of foods become modest and practical, suited for a regular family, including the medicinal uses of everyday fruits and vegetables like figs, pumpkins, bananas that were cures to among other things, insanity, venereal diseases and diabetes. By this time, she must have been married, with a family to take care of. Put together, the recipes pry open a domestic space where tastes and choices were quite distinctive within the practice of compiling recipes which was part of colonial learning.

If the cookbook embodied dreams the teenagers may have harboured about their futures, reality belied them. While Prabhabati was raised in an urban home, she was married into a large rural household of the Guhas, in the adjoining district of Faridpur to a fair, good looking graduate who worked for the British government in the Audit and Accounts department. Prabhabati did not take the transition to the rural setting kindly for all the uncomfortable adjustments she had had to make, but she got to travel and live in cities like Rangoon3, Shimla, Allahabad, Calcutta, with a few years in the steel town of Bokaro. Hers wasn’t an affluent household and certainly not one that could afford an elaborate table for stylish guests. Didi, the eldest, was married to another family far away from Dhaka and they never met again. Shortly after her wedding, the siblings lost their Ma and even though Prabhabati did visit her father and came home to attend her youngest sister’s wedding, the happy days had been left behind.

There was to be another three decades before the British left India in 1947, two nations created, Dhaka becoming part of East Pakistan. The Dutts had long gravitated towards better opportunities in the western part of Bengal, in and around Calcutta. The eldest brother would have already moved to the capital to complete his higher education, when the notebook was being worked on. When she joined him, Indulekha, his strikingly beautiful and poised wife, Boudidi to the rest, became the matriarch to a large family of her own in Calcutta, that continued the tradition of affluence of the Dutts of Dhaka. Her tall, distinguished husband, Nripendra Kumar Dutt, a scholar joined the Sanskrit College, rising in ranks to become its Principal, the second non Brahmin to hold the position till then. His book on the Origin and Growth of Castes in India published from London in 1931 was a seminal work, forming the basis of the next British Census Report4

What of the other siblings? I have no knowledge of the brothers’ academic accomplishment, but it appears that they were both technically qualified. TKD retired from Hindustan Motors, India’s first car manufacturing company and RKD from the Gun and Shell factory. While the latter had been established by the British and the transition after 1947 would have been easy, Hindustan Motors started as late as in 1942 in a small village on the banks of Hugli, not far from Calcutta and what had engaged TKD for 20 years or more before that is lost in the fog of family amnesia.

The youngest Niharbala was married to an engineer in the Steel plant in Jamshedpur and like Indulekha became an accomplished matriarch of an even larger family that she managed with a deft hand. She was perhaps the only one to entertain with some degree of lavishness.

The saddest fate was set aside for the fairest of them all whose beauty matched the legends and earned her the name. Through a network of matchmakers the fame of Helen’s looks reached a prosperous landlord family in Taki, an estate 200 km south west of Dhaka. As was customary, if the groom was from a family of higher social and economic status, the bride was carried away to be married in his house. Helen entered the affluence and comforts of the palatial home but found little happiness. Denied children, she was extremely lonely, seeing little of her busy, politically active husband. He died young and Helen did not survive him for long. Prabhabati who was very close to her sister was shattered when the news reached Rangoon.

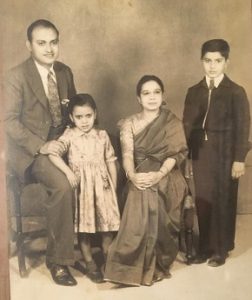

The Green Notebook became part of Prabhabati’s gift to her doting daughter Leena, who was married to a fully commissioned officer in the British Indian Army, much to the mother’s pride and happiness. She married Sushil Chandra Roy on the 16th of August, 1946 in Calcutta, two days after the worst communal riots the city had to witness in Beliaghata, the neighbourhood which was the nerve centre of the conflict-a story waiting to be told.

The last 10 pages of the green notebook are in Leena’s hand, recipes of cakes, sherbets, pickles. As a fulltime army wife, she had to entertain and hold dinners which were dominated by western dishes, baking and roasting. Two recipes in English were of homemade lemonade powder and lemon cream. I don’t remember having either but Ma was known for her innovative chicken dishes, her baking and different kinds of puddings in the western culinary fashion.

recipes of cakes, sherbets, pickles. As a fulltime army wife, she had to entertain and hold dinners which were dominated by western dishes, baking and roasting. Two recipes in English were of homemade lemonade powder and lemon cream. I don’t remember having either but Ma was known for her innovative chicken dishes, her baking and different kinds of puddings in the western culinary fashion.

So many entangled pasts make up the green notebook; so many possible directions the threads of stories can lead to, so many layers of private lives and public histories of culture and communities, of choices and compulsions, of intertwined personal and national destinies still remain to be told.

Tapti is an independent scholar and the editor of Pastconnect.

Footnotes

- Both the Nawabship and the requirements of law were closely connected to the British colonial rule. The Nawabdom was a British creation and therefore the laws it had to conform to, one can assume were colonial too

- Measures such as tola and anna were used instead of ounce or gram

- Yangon. Her great granddaughter wrote about their lives in Burma in https://www.pastconnect.net/the-guhas-of-brooking-street

- After the death of his eldest son, he turned to spiritualism and left home for an ashram